By the middle of the nineteenth century, Concord had just turned 200 years old and had a population of around 2,000. Always a farming town, by the 1840s, Concord’s agricultural economy was in flux, and the crops and farms that had been so important to the town in its first 200 years were evolving. By the dawn of the twentieth century, Concord agriculture had changed in many ways, from the people who were farming to the crops they were growing.

In the 1820s, Concord was at the forefront of agricultural reform. The recently formed Society of Middlesex Husbandmen and Manufacturers promoted “the encouragement or improvement of agriculture,” and membership included not only the landed gentleman farmers but the working farmers that historian Robert Gross calls the “bone and gristle” of the town. The Society began holding its annual cattle shows in 1820, including agricultural exhibits and competitions in the county courthouse, with local farmers like Ephraim Wales Bull showing off their agricultural marvels.

By the 1830s, urban markets like Boston were starting to dictate what the farmers in the country were growing. The completion of the Middlesex Canal in the early nineteenth century meant that Concord farmers could now get their products to Boston faster and more efficiently. Life had changed for them; the ways their fathers and grandfathers had tilled the land were no longer effective or efficient. The old methods of farming “by halves – half-farming, half-cultivating, and half-manuring” – may have worked in 1775, but techniques were changing. It was time, agricultural reformers beseeched, “to break the power of habit and the charm of hereditary custom.” The modern farmer began to consult agricultural periodicals devoted to new farming methods, and they adopted the best new practices. New tools, such as the cast-iron plow, and agricultural techniques, like the use of chemical fertilizers, brought Concord’s farmers squarely into the modern nineteenth century.

The main problem facing Concord was an increasing lack of tillable land. What had been farmed for more than a century was wearing out, and a growing population was using up almost all available farmland. Concord’s agricultural system was based on the usage of grasses, cattle, and manure, and Concord’s pastureland was declining in productivity. As an old adage stated at the time: “No grass, no cattle. No cattle, no manure. No manure, no crops.” Meadows and grasslands were essential to Concord farmers. Upland hay fields (the so-called English Hay) and lowland meadow grasses fed their cattle year-round, and collecting these grasses throughout the summer and into the fall was a time of almost continuous hard work, sweat, and worry. Henry Thoreau would comment in his journal, “There is no pause between English and meadow haying.”

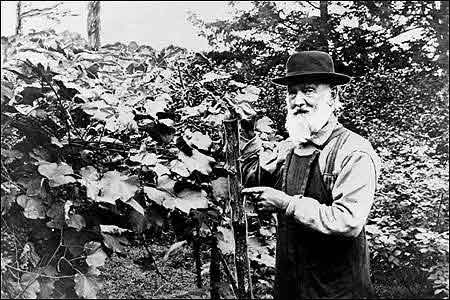

Ephraim Wales Bull and his original Concord grapevine

| commons.wikimedia.orgAnother important aspect of a farmer’s property was his woodlot. Not only did it provide firewood for the family, but it was also used as wooded pasture for cattle, sheep, and even pigs. Surprisingly enough, the vital importance of these woodlots does not mean that they were managed in a thoughtful or careful way. The constant need for firewood had thinned these lots by the nineteenth century, and, as a result, firewood was becoming scarce. Thoreau reported that he could not go anywhere day or night without hearing the sound of an ax, and by 1850 only 10% of Concord was wooded. “Thank god they cannot cut down the clouds,” Thoreau would write.

Another problem that faced Concord farmers in the decades before the Civil War was an exodus of young people from the country into the growing urban areas. Why toil away at a small farm in Concord when the textile mills in Lowell and Lawrence offered better wages? The west was also draining laborers away from New England. The farmlands of Concord and Massachusetts just couldn’t compete with the rich soil of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. As historian Robert Gross would note, by the 1840s “western grains were already winning the day in Boston markets.”

Cattle continued to be the mainstay of Concord’s farmers: salt beef and tanned hides were still in demand outside of Concord, especially in Boston. Once the railroad came to town in 1844, beef, butter, cheese, and milk could be shipped to Boston much faster, and by the 1850s, Concord was a town of dairy farmers. But with the increase of cattle came the increased need for English hay to feed them, and Concord’s grasslands were being expanded by clearing wetlands and woodlots.

By the second quarter of the nineteenth century, Concordians began farming crops primarily for outside markets, a massive change from the subsistence farming of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Whereas corn and rye were grown in abundance in the eighteenth century, the railroad was now bringing affordable wheat flour to town. While living at Walden Pond, Thoreau specifically made a point of making his bread out of cornmeal and rye, the old johnnycakes of the eighteenth century. Why spend money on wheat flour, he wondered, when you can make bread from crops meant for cattle and pigs? He saw the effect the railroad had on Concord’s agriculture: the influx of food items from other parts of the country led New England farmers to become increasingly specialized in what they could offer to outside markets.

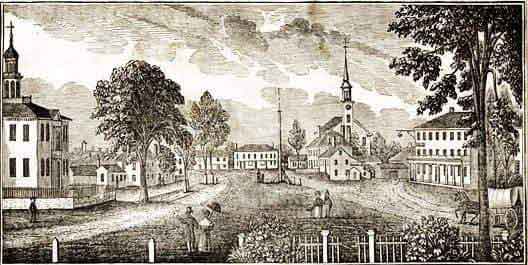

Central Part of Concord, Massachusetts by John Warner Barber; 1839.

| Public domainAs Concord’s farms became more dependent on these markets, it became essential to hire more farm labor. In the years after the Civil War, most native-born Yankees were not willing to work on farms, but new immigrants from Ireland, Canada, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Italy were. And along with those new immigrants came new produce. Among those new crops was asparagus. The rich, fertile, well-drained soil of the Sudbury River valley was well-suited for growing it, and it became an important crop in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. According to farmer Steve Verrill, “the railroad came through Concord to Boston making for quick and easy delivery of the very fresh, early spring crop to a lucrative market. At one point, Concord produced 50% of the Massachusetts crop, and it was the leading producer of asparagus in the entire country.”

By the 1890s, the agricultural landscape of Concord was virtually unrecognizable from how it looked in 1800. Dairying and market-gardening, including the growing of asparagus and strawberries, became important specialties in Concord, and smaller farms were replacing larger ones as usable pastureland continued to shrink. As wood and farm products diminished in importance, land-use trends were reversing. Pastures shrank, and woods expanded onto stony sites covering 40% of Concord by century’s end. Along with these increasing woodlands was an increase in wildlife; animals that Henry Thoreau never saw, like deer, turkey, and beaver, began reappearing in Concord’s slowly regrowing woodlands.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Concord exceeded its carrying capacity. The town became so densely populated that its residents could no longer live sustainably on its 25-square-mile land. Concord went from a relatively self-sufficient community to a town highly dependent on outside resources. This was the world Concordians faced at the dawn of the twentieth century.