There’s nothing like getting wrapped up in a good cozy mystery. For the Agatha Christie lover, true crimes close to home are particularly enlivening. At Concord’s Old Manse Museum, home of the famous Emerson family and witness house to two revolutions, there lurks an unsolved puzzler.

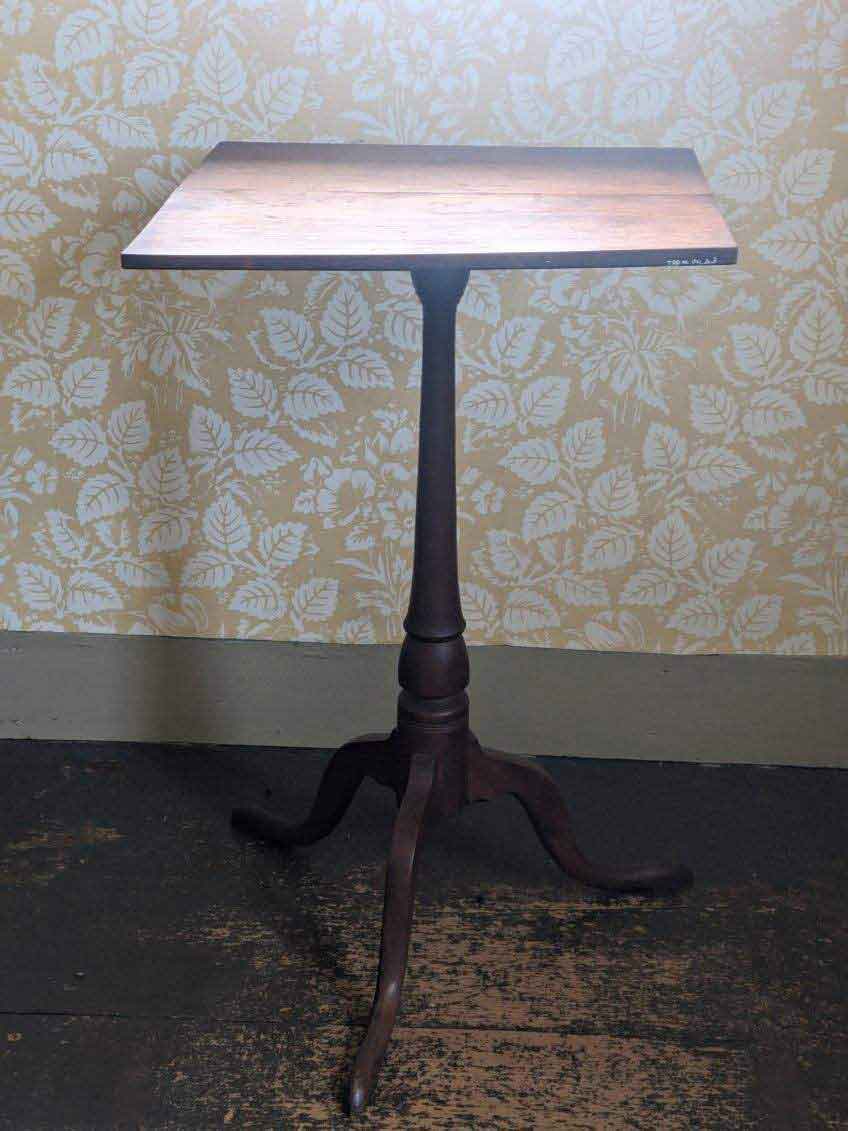

Thousands of people come from around the world each year to visit The Old Manse. Guided tours offer visitors an opportunity to learn the history of the 253-year-old Gambrel Colonial-style home and get an up-close look at the original heirlooms and artifacts used by its historic occupants. Every teacup sipped in, every bed slept on. Family portraits hang above mundane objects that sit upon priceless tables. A seventeenth century grandfather clock, the heartbeat of the house, has continued to chime away the hours since 1770, when the Rev. William Emerson, the Patriot Minister of the American Revolution, placed it in his new study. Sophia Peabody Hawthorne engraved an ode to her husband, Nathaniel, in the same room where Ralph Waldo Emerson sketched out his famous writing, Nature. Down through the ages, the families dwelled until they finally sold the historic home to The Trustees of Reservations in 1939.

Courtesy of the author

Courtesy of the author Courtesy of the author

Courtesy of the authorOn September 2, 1968, the Old Manse received unwelcome visitors. In the dark of night, vandals parked a truck yards away at the rear of the homestead and went on foot over the famous stone walls that border the North Bridge. By climbing the roof of a shed attached to the home, they entered a second-floor window. Before dawn, they left through a side door with about thirty historic antiques of irreplaceable worth – a mahogany Sheraton writing desk, a claw-and-ball-foot Chippendale corner chair, several Queen Anne dining chairs, and a block-front mahogany desk valued that year at $15,000. Room to room they crept with deliberation, taking the most exclusive pieces and leaving without a trace.

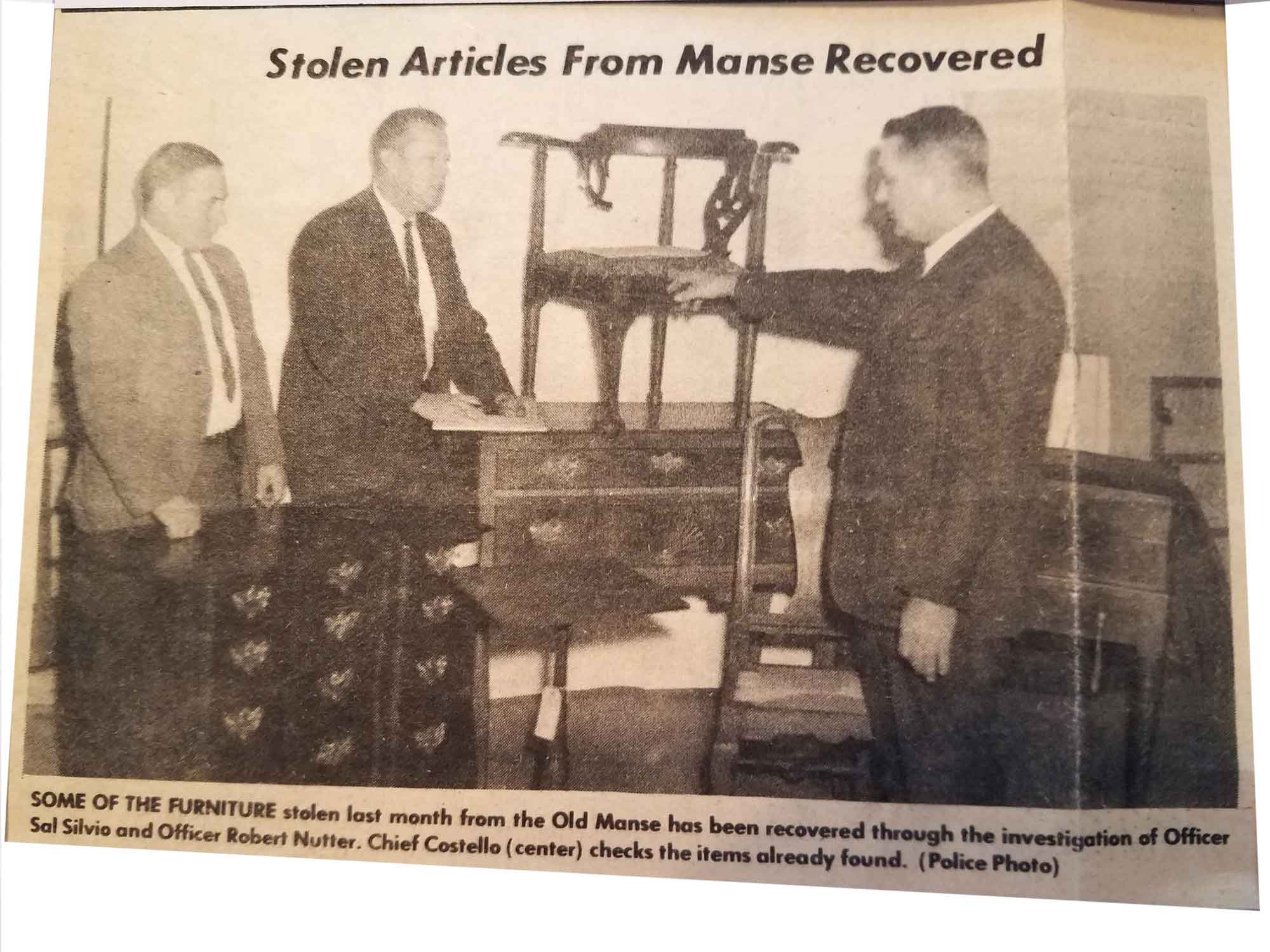

The break was discovered the next morning by a part-time employee who alerted the Concord police. As reported by The Concord Journal in October of 1968, “The clues were slim, the trail cold. Inspectors W. Robert Nutter and Salvatore C. Silvio were assigned to the case.”

“We knew nothing about antiques,” Inspector Nutter acknowledged, “and we didn’t have a lot of time to learn. All we knew for sure was that we were not up against ordinary burglars. Those guys knew what they were doing.” While puffing on his pipe, Inspector Silvio added, “We were told it would be next to impossible for us to make a recovery.”

With no leads and nothing but a few photographs from Old Manse records, the two set out in an aging truck in search of clues. Over the next thirty days and more than five hundred hours of overtime for which they did not seek compensation, the sleuths stopped at nearly every dusty antique shop and auction house throughout New England. At one point, they were even taken as hold-up men by a guard at an exclusive auction in Connecticut. “He knew there was something different about us. Sharp fellow,” Silvio commented. As the weeks went by, the men knew their chances were slim. Antiques then, as now, can move fast from dealer to dealer, particularly when their provenance is in question. The inspectors were told that once sold into private homes, pieces would be nearly impossible to retrieve.

Courtesy of the author

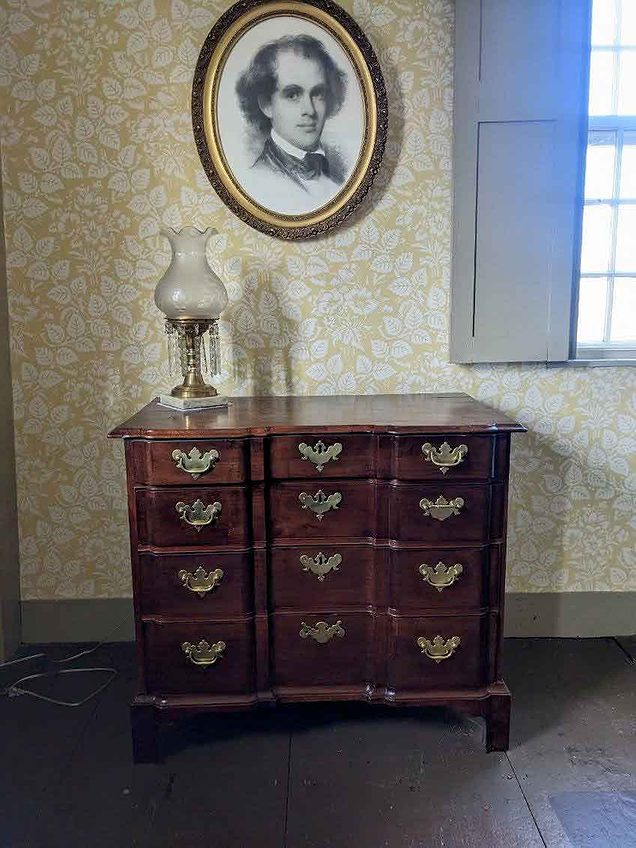

Courtesy of the authorIn a small town in western Massachusetts, their efforts were rewarded. After showing a photograph of a corner chair, the dealer responded that he had seen it. “He made immediate arrangements for us to meet a couple of other dealers,” said Nutter in a moment of what must have been pure pleasure. By back-tracking on sales, travelling from shop to shop, the officers were able to recover most of the pieces, including a chest of drawers that was within hours of being loaded onto a truck headed for Ohio. They discovered the corner chair that had been sold three times within two weeks in two states. According to their report, they encountered, for the most part, antique dealers who were eager to help. They came to understand that there was a strong sense of history and a keen interest in having relics returned to their proper places. Although some dealers were knowingly handling stolen goods, the officers lacked the necessary and substantial proof to press charges.

An eighteenth-century Sheraton mahogany chest is still missing, as well as some smaller household items, leaving Nutter and Silvio with some regret. Silvio stated, “After so much work, I would have gone to China to get that chest.” Emerging with a vast knowledge of the underground antique trade, the two Concord police officers earned glowing reputations. “We got requests from all over,” Silvio said. “Police departments from many states have called us…I used to think jewelry thefts were big stuff. They can’t compare with what goes on with antiques.”

Without a doubt, these detectives turned out an astonishing performance in the mystery of The Old Manse. The stunning pieces are back where they belong, in a home that silently speaks of our nation’s great past. Wherever the missing chest resides, here’s hoping the will and determination of Officers Nutting and Silvio inspire a twenty-first century sleuth to assist in its return.

Acknowledgements:

Concord Journal, Thursday, October 7, 1968

Yankee magazine, May 1969

-(1).png?height=300&t=1723217972)