The Massachusetts Court Closures of 1774 marked the escalation of Massachusetts’ resistance to British authority. The closures were a direct response to the Coercive Acts (also known as the Intolerable Acts), a series of punitive measures passed by the British Parliament in 1774. Among the measures was the Massachusetts Government Act, which severely restricted colonial self-governance by placing the judicial system under the direct control of the royal governor and eliminating town meetings without prior approval. Many colonists believed that this act infringed their rights and autonomy as British citizens.

In the summer of 1774, resistance to the Coercive Acts reached a boiling point. Across Massachusetts, local committees of correspondence began organizing efforts to minimize and defy British authority. A letter from General Thomas Gage, the royal governor of Massachusetts, to Lord Dartmouth, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, vividly illustrates the scope of the resistance. The general wrote on September 2, 1774: “In Worcester, they keep no Terms, openly threaten Resistance by Arms, have been purchasing Arms, preparing them, casting Ball, and providing Powder, and threaten to attack any Troops who dare to oppose them….the flames of sedition spread universally throughout the country beyond conception.”1

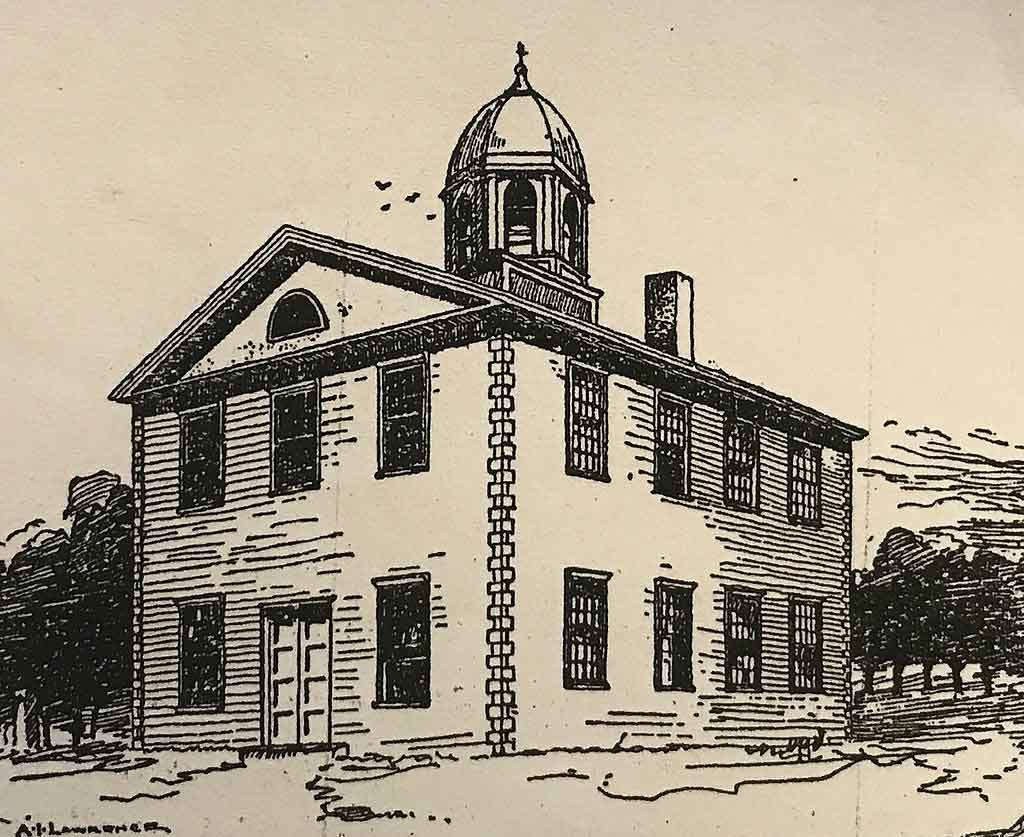

An early target of the resistance movement was the colony’s judicial system. On August 16, 1774, more than 1,500 armed colonists gathered in western Massachusetts to shut down the county courts in Springfield and Great Barrington. A few weeks later, over 4,000 militiamen marched on Worcester. When the Crown-appointed court officials arrived to begin court proceedings, barricades had been erected, preventing them from opening the courthouse doors. Worcester’s Committee of Correspondence attempted to develop a compromise, which the leaders of the various militia companies quickly rejected. While each company stood in formation, the heads of the militias headed to the house of Timothy Paine and demanded that he resign from his appointment to the court. In the mid-afternoon, the dozen court officials emerged from Daniel Heywood’s tavern. They signed papers disavowing British authority and resigning their positions, repeating the disavowal to each assembled militia company.2 Similar actions occurred in Plymouth, Essex, Norfolk, and Middlesex counties.

The closure of the courts was not a haphazard uprising but a coordinated and deliberate act of civil disobedience. The protestors viewed the judicial system as illegitimate under the new regulations and sought to prevent its functioning until colonial rights were restored.

The Massachusetts court closures demonstrated the colonists’ ability to organize and execute resistance on a large scale, thereby undermining British authority in the region. Additionally, they galvanized support for the broader revolutionary cause as other colonies observed Massachusetts’ defiance and joined in solidarity. Finally, the closures exposed the limitations of British power in enforcing unpopular laws.

Notes:

1 Gordon Harris, “‘A State of Nature’, Worcester in 1774,” Historic Ipswich, January 6, 2025, https://historicipswich.net/2022/12/05/a-state-of-nature-worcester-in-1774/.

2 Gary Hunt, “The End of the Revolution and the Beginning of Independence - Social Upheaval in Colonial America: 1774-1775,” Outpost of Freedom, February 2, 2010.