A week before Thanksgiving 1917, the Concord Enterprise printed a letter from a young Maynard man named Hugh Connors. The United States had entered the First World War seven months earlier, and Connors had shipped out with New England Sawmill Unit No. 3, a team of American lumbermen stationed in Scotland.1 “I am writing this letter in bed,” he wrote, “as I have been laid up for a week with the grippe. Over here they call it influenza,” he added, as if translating a foreign word. “I am not at the hospital, but have engaged a room about five minutes’ ride by bicycle, from our camp.”2

He didn’t seem too worried about his illness. His bunkmates, felling trees to supply lumber for the war effort, probably mocked him as he pedaled off to his cozy sickbed. Friends and family back home never suspected that this might be their first warning of an imminent global tragedy.

The first wave of the influenza pandemic took its heaviest toll among the oldest and youngest populations. Fit young adults like Hugh Connors often recovered quickly. Americans knew little about the disease, because wartime censorship kept the European press from reporting on it. Spain remained neutral, so the Spanish press were free to document the outbreak, leading many to refer to it as “Spanish flu.”

New England Sawmill Unit

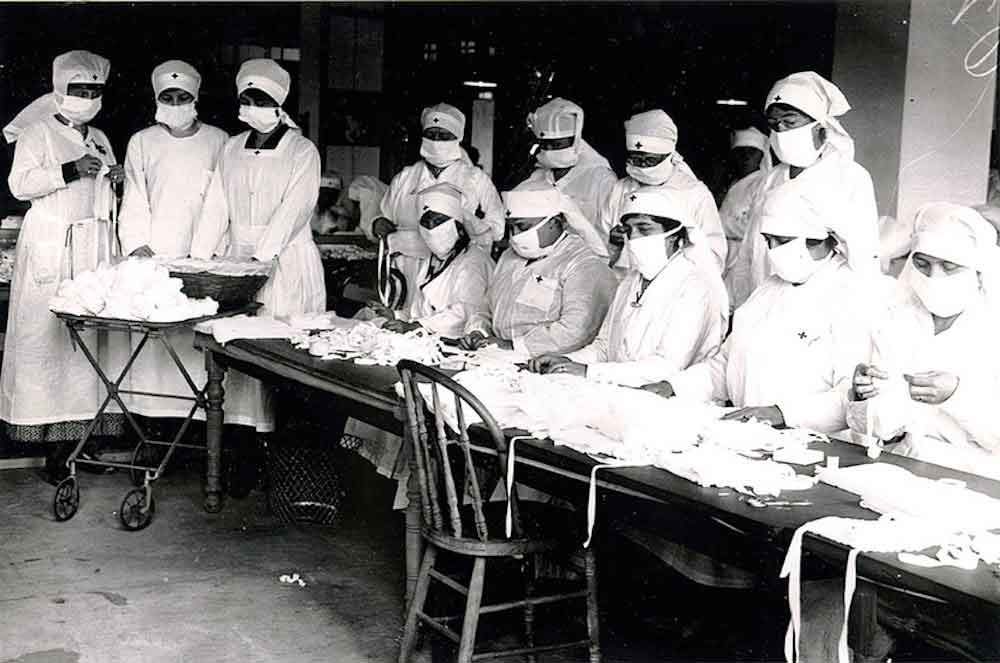

| ©Acton Historical SocietyIn March 1918, a case of influenza was reported at Fort Riley in Kansas, and quickly spread as soldiers were moved from base to base. In the late summer, a more lethal strain of the flu emerged, and Concord found itself dead center between two of the U.S. hot spots, less than 20 miles from both Boston Navy Yard and Camp Devens. On September 20, a soldier at Devens died “after but a few hours’ illness [of the] influenza now so prevalent among both soldiers and civilians.” A Red Cross nurse attending the sick at Camp Devens was another victim.

In September 1918, Maynard reported “200 cases under treatment.” In three weeks that number had jumped to more than a thousand, and “churches of every denomination were closed” as advised by health authorities.

Concord closed its schools for the month of October, and Acton, Maynard, and other nearby towns followed suit.

Concord’s Board of Health documented “between 250 and 400 cases” of the flu, including 25 fatalities, in mid-October. They noted an encouraging trend over one weekend when “On Friday there were 21 new cases, on Saturday nine, and from Saturday until Monday only 7,” but warned against a false sense of security, declaring “Every precaution should be taken by all to help check this epidemic.”

Pharmacy Advertisement from Concord Enterprise, Oct 2, 1918

| Public domainThe Massachusetts State Department of Health issued familiar guidelines: “Wash your hands before each meal. Smother your cough in your handkerchief. Avoid the person who coughs or sneezes. Don’t go to crowded places. Walk to work if possible.” Other recommendations were to stay warm, avoid dampness, and get plenty of fresh air and sunshine, all thought to help fight off the flu.

A Maynard pharmacist ran a prominent newspaper advertisement urging readers to “prevent disease” with a “Disinfectant, Germicide, and Antiseptic” called Sulpho-Tol, perhaps the Purell of its day.

State, county, and district elections were just a few weeks away, but the Concord Enterprise noted that they stirred up little interest, because “the minds of the voters are occupied with news of the war, [and] the ravages of the influenza epidemic.”

Even those who escaped infection felt the impact of the epidemic. The flu took a devastating toll among coal miners, and local residents were urged to “save what anthracite you can” because coal was in short supply. The Concord Board of Health noted the town experienced food shortages and “unsatisfactory” garbage collection due to widespread illness of workers.3

School Superintendent Wells A. Hall worried over how to make up the students’ progress lost over the four weeks that schools were closed due to the epidemic. He toyed with the idea of prolonging the school year to July 4, but wisely concluded “we shall get only diminishing returns.”4

By the beginning of November, the epidemic was thought to be “almost at a standstill, there being but a very few new cases reported.” Schools reopened and a headline declared “Places May Open for Business Monday—Danger Thought to Have Passed.”

Residents’ optimism was premature. In January 1919, the flu surged back with “[m]any new cases” in Concord, Acton, Bedford, and Sudbury. Acton and Boxboro closed their schools. The dedication of the new Harvey Wheeler School was “indefinitely postponed” due to influenza. (It would eventually take place on March 12.) The Concord Enterprise warned its readers, “There is considerable danger at the present time, as influenza is paying Boston and vicinity a return visit. Do not neglect a cold, and beware of coughers and sneezers.”

By mid-February the outbreak had subsided, and Concord and its neighbors paused to reflect on what they had learned from this trauma. The Town of Maynard acknowledged that the restrictions placed on businesses, though unpleasant, were “for the common good of the community.”

“Much was accomplished but still more could have been done by earlier organization,” the Concord Enterprise observed. The American Red Cross proposed taking a Survey of Nursing Resources, a house-to-house canvass to identify those “capable of giving assistance in the care of not only the Army but the great number of those who must remain at home.”

Concord expressed gratitude not only to government agencies, but to private citizens and nonprofit groups who had stepped up to the help those afflicted by the epidemic. The Board of Health declared that the “real work of taking care of the victims of this epidemic was undertaken by the Women’s Charitable Society, with the aid of the Red Cross . . . obtaining nurses, opening of food kitchens, and carrying food to the homes where all were stricken.”5

Concord in 1918 shows us valuable examples of how to follow good health practices and work together as a community to face a crisis.

NOTES

1 actonhistoricalsociety.org 2 This and other text quoted from issues of the Concord Enterprise, 1917-1919, archived by the Acton Memorial Library. 3 1918 Concord Town Report, courtesy of William Munroe Special Collections, Concord Free Public Library. 4 Ibid. 5 Ibid.