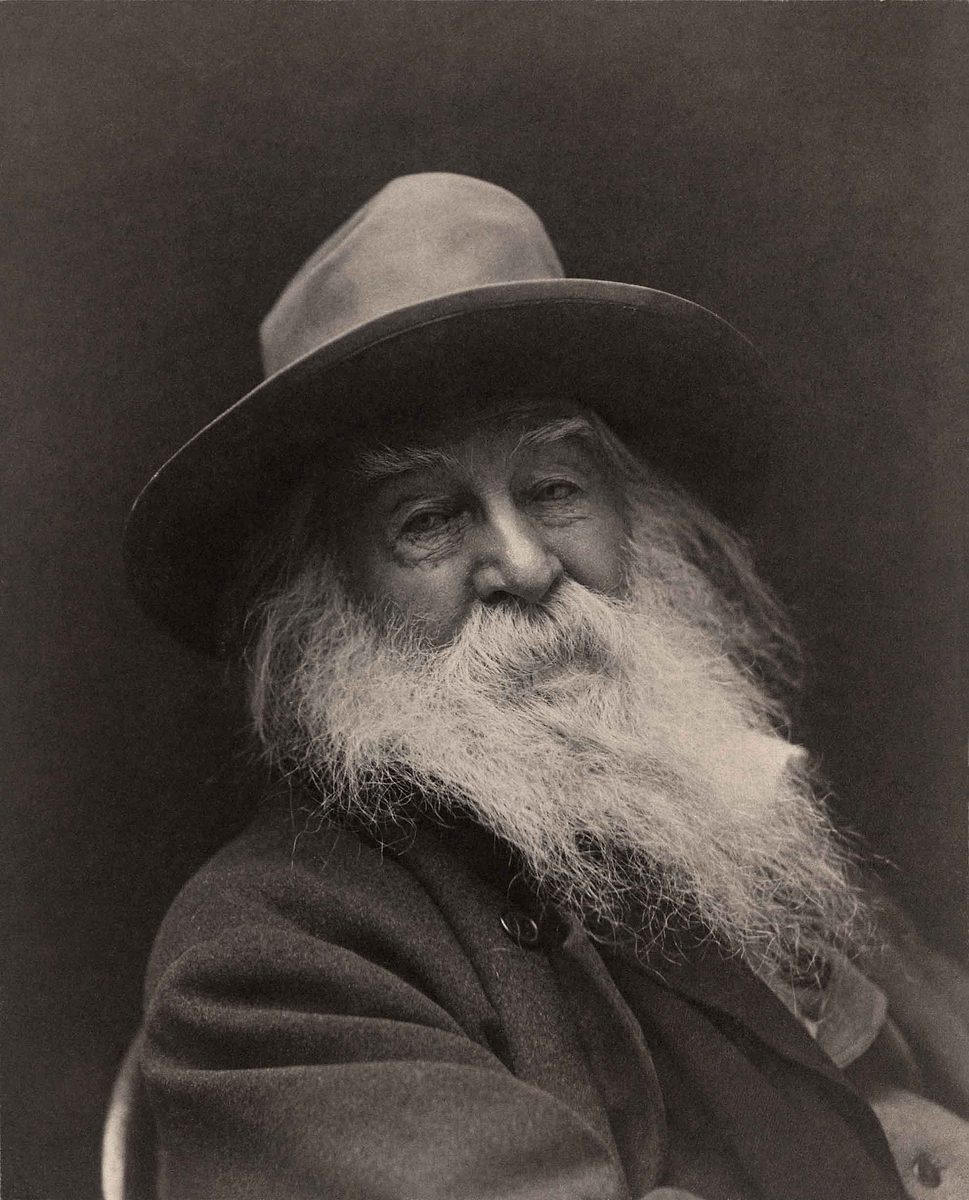

I believe a leaf of grass is no less than the journey-work of the stars

Walt Whitman, Song of Myself XXXI

In 1855, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote a letter that would become one of the most famous pieces of correspondence in American literary history.

That year was a difficult time for the adolescent country. Already sharply divided over the issue of slavery, “free soilers” and pro-slavery factions were quickly disintegrating into bloody violence. The ongoing gold rush and westward expansion was continuing to displace native populations, while the same year, and without irony, a white, anti-immigrant party in Cincinnati would attack a local German-American neighborhood for being foreigners.

In Concord, Emerson’s wife Lidian protested the state of the Union and slavery by hanging black bunting from their house on the 4th of July. Thoreau was ill almost that entire year and Waldo fretted about his friend’s decline. Hawthorne and his family were away in England, and the Alcotts were scattered, still a few years away from taking up residence at what would become Orchard House.

In this anxious environment Emerson received a thin book of poems, anonymously sent from New York, but bearing the name Walter Whitman along with that of the publisher. This was the first edition of Leaves of Grass. To Emerson, that little book of poetry was a direct answer to a call that was issued more than a decade previously.

In his 1844 Essays: Second Series, Emerson had included an essay called The Poet, in which he expressed the need and desire for an American Poet - a voice that was so encompassing and powerful that it could be representative of the country as a whole.

“The poet is the person in whom these powers are in balance, the man without impediment, who sees and handles that which others dream of, traverses the whole scale of experience, and is representative of man, in virtue of being the largest power to receive and to impart,” he wrote.

In that tense July of 1855, Emerson felt he had finally found his Poet and a few days later wrote to the 36-year-old Whitman, saying “I greet you at the beginning of a great career…I am not blind to the worth of the wonderful gift of Leaves of Grass…” Emerson then delivered his highest compliment, stating “I find it the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed.”1

The letter would eventually be published (without Emerson’s knowledge) and would serve to ensure the book’s success. In later years, there would be some backtracking by both men with Emerson asking the poet to tone down some of the volume’s explicit sexual references, and with Whitman later denying Emerson was ever an influence, despite a mountain of evidence to the contrary.

Regardless of their eventual disagreements, the gentle transcendentalist and the rough New York native were now inextricably linked to each other and to American literary history. The Sage of Concord called, and was answered by the first “poet of democracy” - a man who spoke not as himself, but as the voice of the country, in all its horror and glory, its beauty and sorrow. Or as Whitman famously put it in Song of Myself, his epic ode to America,

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

1 Letter, Ralph Waldo Emerson to Walt Whitman extolling Whitman’s poetry, 21 July 1855. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mcc.012/.