There are places where you can stand for a moment between worlds. Concord Center’s Main Street is one of them. Over it, on April 19th, 1775, British officer Major John Pitcairn crossed from a world securely under English sovereignty and into one at war, fast on its way to American Independence.

Pitcairn’s road to Concord started in Scotland where he was born in 1722. Scotland was divided with some Scots (Jacobites) loyal to an exiled King James Stuart, others (Loyalists) to the reigning monarch King George II. Pitcairn’s father was a local minister, and although family lineage traced back to ancient Scottish King Robert the Bruce, the Pitcairns were loyal to King George. In his twenties, Pitcairn joined His Majesty’s 7th Marines of Cornwall and soon found his regiment involved in the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745.

This rebellion ended with the Jacobites’ defeat at the Battle of Culloden in 1746. After the battle, legend tells of two Jacobite brothers, one mortally injured, awaiting execution in England’s Carlisle prison. Knowing he would die, the injured man told his brother to escape without him, saying, “‘You take the high road, and I’ll take the low road, and I’ll be in Scotland before you.” His words referenced the old Celtic belief that the spirit of a soldier who died in a foreign land would be carried home on “the low road” through the fairy world, an unseen place below the “high roads” of the living.

With the rebellion over, Pitcairn returned home, married, and had a large family before he was sent to Canada in 1755 during the French and Indian War.

Around that time, unrest was growing in America, the colonies divided between Loyalists and Patriots favoring independence. After the 1773 “Boston Tea Party,” Parliament sent a full army to occupy Boston and quash further rebellion. In 1774, Pitcairn, now a Major, was dispatched from Canada to Boston to command 600 marines.

istock.com/northwoodsphoto

istock.com/northwoodsphotoUpon arrival, Pitcairn discovered a disorderly bunch; the marines were bored and drunk. In Pitcairn’s words, the men were “animals”— and they were short. Pitcairn wrote to the Earl of Sandwich, “I am a great deal hurt and mortified to find the marines so much shorter than men are in the regiments.” Complained Pitcairn, why couldn’t he have anyone over 5’6” tall?

Pitcairn sobered and hardened up his “animals” with marches through the countryside and disciplined drills. His justness and interest in each man soon earned him their respect.

Fondness for Pitcairn extended into the Colonist community. Pitcairn was billeted with Francis Shaw, an ardent Patriot and neighbor of Paul Revere. Despite their political differences, Shaw observed Pitcairn’s pleasant demeanor and fairness, especially to Shaw’s son whom Pitcairn saved from a duel. In Shaw’s house, Pitcairn hosted gatherings between British officers and Patriots, allowing civil discussion of their differences. Ever the minister’s son, Pitcairn attended Boston’s Old North Church services and was known as a holy-tongued man on Sundays who could swear like the devil Mondays through Saturdays.

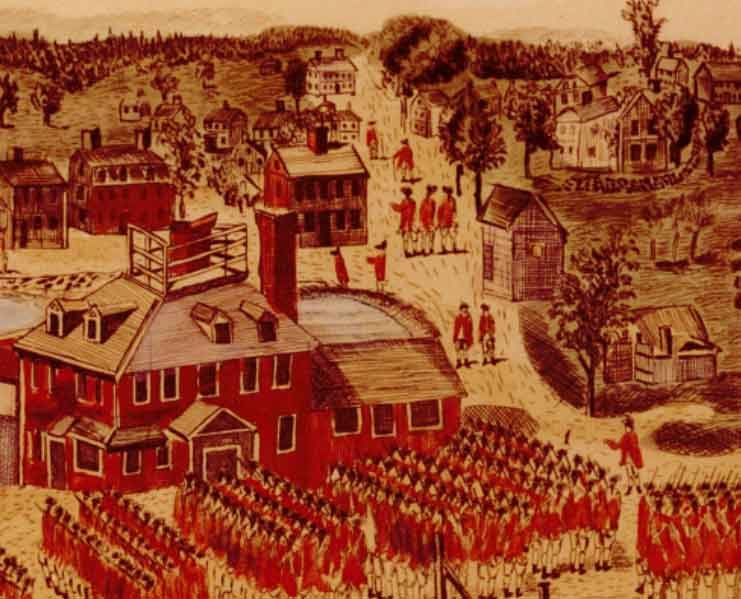

The latter vocabulary would flow freely on April 19th, 1775, when General Gage dispatched Lt. Col. Smith and the King’s troops to Concord to find and destroy a military stockpile. Pitcairn volunteered to go and led the front column. Arriving near dawn in Lexington, they encountered armed Minutemen on the town common. Pitcairn demanded the colonists lay down their arms and disperse. An unknown shot rang out and firing commenced from both parties. Under orders not to harm citizens, Pitcairn shouted for the English soldiers to cease fire, but by the time order was restored, eight colonists had been killed.

The regiments pressed on to Concord where they split up to search the town, and Pitcairn and Smith went into two taverns in Concord Center. Gathering places for local militia, minutemen, and members of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress (then headquartered in Concord’s meeting house), the taverns were the place for information.

While Lt. Col. Smith set up a command post in the Wright Tavern (located by the town green), Pitcairn hastened up Main Street to Jones’ tavern. Now no longer in existence, Jones’ tavern was located near the South Burying ground (by Main Street and Keyes Road) and owned by town representative and jailor Captain Ephraim Jones.

Banging on the door, Pitcairn demanded Jones open-up! Jones refused. Brigadiers broke down the door, Pitcairn stepped through, and knocked Jones to the floor. Bellowing threats, Pitcairn pressed his pistol to Jones’ throat and demanded he reveal the stockpile location.

At gunpoint, Jones led Pitcairn to the jail yard, where, too heavy to quickly hide, there remained three 24-pounder cannons; each approximately ten feet long, 6,000 pounds, and capable of bombarding a city. Supplies needed to operate the cannon were also present. Pitcairn ordered their destruction. Trunnions were removed, and wooden trenchers, spoons, and sixteen carriage wheels piled in the town center and burned.

Business done, Pitcairn released Jones, accompanied him back into his tavern, ordered breakfast for his men, and paid in full.

Meanwhile, outside, things were not going well. Embers from the burning supplies set the town house roof ablaze, and the fight occurred at the North Bridge.

Frantic messengers alerted Pitcairn to the trouble and panicked regiments retreating from the bridge. Rapidly retracing his steps over Main Street, Pitcairn joined other officers struggling to maintain order during a day-long running battle from Concord back to Boston.

On June 17th, 1775, worlds again crossed for Pitcairn in what today is called the Battle of Bunker Hill. Climbing the blood-slicked hillside, Pitcairn raised his sword, shouted, “For the glory of the marines!” and led the charge uphill. Pitcairn was shot but pressed on until he fell. His son William (a marine Lieutenant) carried him from the field.

As Pitcairn died, his marines— whom Pitcairn developed into the bravest of His Majesty’s forces— took the hill and won the day for England.

Cried William in despair, “They have taken my father!” Echoed the marines, “He was all our father!”

Pitcairn’s death was grieved by Loyalists and Patriots alike. Wrote Colonist Ezra Stiles, “He was a good man in a bad cause.” Pitcairn was buried in Boston’s Old North Church crypt. Years later, his Scottish family paid a Bostonian (locally regarded as a swindler) to send Pitcairn’s remains home. It is murky if the correct coffin was sent, but Pitcairn’s descendants believed it was.

The Wright Tavern still stands in Concord Center. It is currently a private building, but next time your road takes you by it and up Main Street, keep an eye out, and maybe, for just a moment, you’ll glimpse Major John Pitcairn hovering between two worlds; one foot on the high road, the other heading towards his low road home.

Source list: email barrowbookstore@gmail.com