Amos Bronson Alcott was about to drown. How could this be happening? Born on November 29th, 1799, he was the eldest son of a poor farmer from Wolcott, Connecticut, and he was only 19 years old! Straining to keep his head above water, Bronson could see his bag on the shore with the $100 he was bringing home to help pay his father’s debts. And what of his mother, who taught Bronson his ABCs by having him trace them on her dirt parlor floor, her warm memory in stark contrast to the rigid teacher in the one room schoolhouse Bronson attended until leaving at age 10 to work full-time on his father’s farm. He had continued to love reading and learning, amassed books, and dreamed of becoming a teacher. At 17, he passed his teacher’s certification, but no teaching positions had yet opened for him and he’d taken to the road as a peddler, joining a “peddling fever” of New England men selling trinkets and household wares through Southern states. On this May morning, in the company of another young peddler, Bronson was returning from his second trip south. Near Williamsburg, Virginia, the two stopped to bathe in the James River. A sudden rip current seized them! Petrified, Bronson’s companion grabbed him, dragging Bronson down until death loosened his grasp. Now, fighting the current alone, perhaps a line from Bronson’s favorite novel, Pilgrim’s Progress, screamed through his head, “What shall I do to be saved?” I shall kick, and I shall swim, and I shall claw my way to shore. And with that, this grandson of an American Revolutionary War soldier saved himself from the James River.

After three more peddling expeditions, Bronson finally attained a teaching job. From 1823-1828, he taught school in Connecticut, applying unconventional methods foreign to the time. Influenced by the Swiss educator Pestalozzi, who promoted individualized, moral, and harmonious education, Bronson believed that children had their own minds and should be taught to think rather than be forced to memorize. He saw inherent goodness in each child, and disdained corporal punishment and the sedentary schools of old. He encouraged students to get out of chairs, act out lessons, and exercise. He also started evening classes for students’ parents. Despite being recognized by area newspapers as a school “of a superior and improved kind” and perhaps the best common school in the United States, some regarded his radical methods with fear and suspicion and his school closed in 1828.

A lifetime of educational pursuits followed. Marrying Abigail May in 1830, Bronson moved to Boston, MA, where, with the teaching assistance of Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, (the brilliant sister-in-law of Nathaniel Hawthorne), he opened and ran The Temple School. In an age where “children should be seen and not heard”, Bronson continued to ask questions of the children, encouraging their self-expression. His methods began to garner public notice and controversy, particularly when Bronson initiated a series of “Conversations on the Gospels” with his young students. For the families, this was an outrageous entering of religion reserved for the church. Backlash against Bronson was fierce, but the Bostonian minister Ralph Waldo Emerson came to his defense calling Bronson a Socrates of his time. Although Bronson was forced to close the Temple School, he began a lifetime friendship with Emerson, which led Bronson to write that, for all the trouble closing the school had brought, having gained the friendship of Emerson made “the hemlock, though bitter… [still] a healthful and invigorating drink.”

Undeterred, Bronson opened the small Beech School. Here, his stand on equality drew further ire. When Bronson admitted an African American child, many of the other children’s parents demanded the child be removed. Bronson, an ardent abolitionist, refused. Approximately half of the families withdrew their students, forcing Bronson to close the school. Despite experiences like this, Bronson continued to live by his principles both as a teacher and in his personal life. For example, one of the Alcott’s homes in Concord was an active stop on the underground railroad, and Bronson was once arrested for refusing to pay taxes that he thought supported slavery, an action that Thoreau emulated years later.

As time continued, financial hardships dogged Bronson and his family, which now consisted of his wife Abigail and children Anna, Louisa, Elizabeth, and May. They moved more than 20 times. Throughout all, Bronson continued intellectual endeavors, including founding the American Transcendental Movement with his friends Emerson, Thoreau, and Margaret Fuller.

In 1857, with assistance from Emerson (who kept a revolving $500 sum referred to as “the Alcott sinking fund”), the Alcotts bought Orchard House, a home next to the Wayside (where they had previously lived).

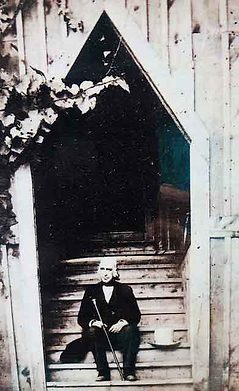

Hillside Chapel (aka The Concord School of Philosophy and Literature). Built by Bronson in 1880.

| Photo by Barrow BookstoreWhile living in Orchard House, Bronson became Superintendent of the Schools of Concord, a position that well suited him. In 1868, Louisa wrote Little Women. The novel was a tremendous success and the Alcotts became financially secure. Bronson was now free to fully pursue the academic life that had called to him since childhood; he traveled throughout the country attending and giving lectures and meeting like-minded scholars such as Transcendentalist William Torrey Harris.

Harris and Bronson discussed opening an educational center for adults, a place of conversation and learning. In 1879, with Concordian abolitionist Frank Sanborn operating as secretary, and William Torrey Harris as consultant and financier, Bronson opened the Concord School of Philosophy and Literature. The first session was held in Orchard House; an enthusiastic crowd crammed into one room.

The following year, Bronson built Hillside Chapel near Orchard House. Reflecting Bronson’s ideas for his earlier classrooms, the building was full of windows, and heated. Church-like, a gabled entry stood ready to welcome visitors who came to hear lectures on many topics, including Transcendentalism and the closely related philosophies of Platonism and Hegelianism.

If the words Transcendentalism, Platonism, and Hegelianism don’t excite you, you have something in common with 19th century Concordians, most of whom viewed Bronson’s School of Philosophy as a waste of time, destined to fail. But when crowds of American and European visitors started coming to attend summer sessions at the School, and were willing to pay for accommodation and food, the town welcomed them! In an 1882 journal entry, Louisa noted this change in Concord sentiment writing, “The school is pronounced a success because it brings money to the town. Even philosophers can’t do without food, beds, and washing.” School of Philosophy speakers included Bronson, Emerson, William Torrey Harris, Elizabeth Peabody, Julia Ward Howe, Emma Lazarus, and more. The school continued until Bronson died in 1888. His eulogy was read in the building and on the mourners’ way out, the doors closed for the final time in the 19th century.

The building was preserved by Concord author Harriet Lothrop (author of The Five Little Peppers series under the pen name of Margaret Sidney) who, when living next door at the Wayside, bought the Orchard House property and used the School as a play-house for her daughter, Margaret. When Margaret inherited the property, she sold Orchard House and the School to a group of women who turned the properties into a museum.

In 1975, the Orchard House museum restored Bronson’s School of Philosophy and started a recurring “Summer Conversation Series” for adult scholars. And now in present day, hopefully soon, Orchard House may once again open those doors to you. Until then, if unexpected tides are threatening to drag you down, perhaps you too will hear the Pilgrim’s cry, “What shall I do to be saved?” and Bronson’s voice will answer, “Follow Your Ideals” and keep swimming.

Select Sources & Recommended Reading:

Shepard, Odell (1937) Pedlar’s Progress, Little, Brown, and Co., Boston, MA

Alcott, Bronson (1850) New Connecticut. An Autobiographical Poem

Alcott, Louisa, (1888) E. Cheney (Ed.) Life, Letters, and Journals of Louisa May Alcott, Little, Brown, and Co., Boston, MA

Joroff, A. D. (1995), Amos Bronson Alcott, Scrap-Baggers, (Vol. 2, No. 2, 1-3)

Matteson, John (2007) Eden’s Outcasts: The Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Father, W.W. Norton & Company, New York, N.Y.