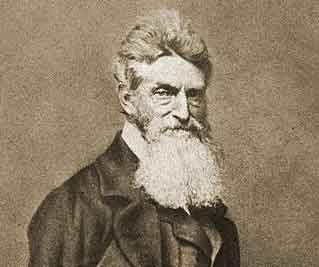

On May 8, 1859, John Brown was back in Concord. The tall, humorless abolitionist had grown a flowing white beard, making him look like an Old Testament prophet. Like he did during his first visit in 1857, Brown spoke on his anti-slavery activities in Kansas to a large crowd at the Town Hall; he had come east in the hope of raising money for those activities. As in 1857, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Thoreau were again in the audience, and they supported Brown; intellectually, philosophically, and monetarily.

The man who brought John Brown to Concord was a 27-year-old schoolteacher named Franklin Sanborn. An 1855 graduate of Harvard College, young Sanborn moved to Concord, was befriended by Emerson, Thoreau, and Bronson Alcott, and was openly admitted into their select company for walks and Transcendental conversation.

Sanborn was also a fanatical abolitionist. By 1856 he had become the secretary of the Massachusetts State Kansas Aid Committee, an organization dedicated to helping anti-slavery emigrants settle in Kansas and make it a Free State. Bronson Alcott called Sanborn “something of a revolutionary” while Henry Thoreau wrote that the young man’s “quiet, steadfast earnestness and ethical fortitude are of the type that calmly...ignites and then throws bomb after bomb.”

By the late 1850s, it was evident to many abolitionists that slavery was not going away; the Fugitive Slave Law, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the attack on Senator Charles Sumner in the United States Congress, and the Dred Scott decision showed many Americans that more drastic measures were needed to bring an end to slavery. When Sanborn met John Brown in 1857, he felt that Brown was just the man to do it. He would later write that Brown’s devotion to Abolition and the principles of the American Revolution were a constant in Brown’s mind; he quoted Brown as saying, “I believe in the Golden Rule and the Declaration of Independence. I think they both mean the same thing.”

Of course, Sanborn was not the only one who would support John Brown; between 1856 and 1859, a small group of supporters would become Brown’s closest confidants and the chief suppliers of the money and weapons that he would ultimately use in his raid on Harpers Ferry. These men, all but one a New Englander, would become known as The Secret Six.

Public domain

Public domainGeorge Luther Stearns and Gerritt Smith were the wealthiest of the Six. Stearns, in particular, was a successful industrialist who lived in a large mansion in Medford, Massachusetts. He personally gave hundreds of dollars for Brown’s activities.

Samuel Gridley Howe was a physician and an advocate of education for the blind; he was instrumental in the creation of the Perkins Institute for the Blind in Watertown, Massachusetts. He was also married to Julia Ward Howe, who is best remembered for writing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” in 1861.

The last two members of the Six, Theodore Parker and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, were Unitarian ministers who, like Sanborn, had close connections to Concord. These men of God were the most radical of the group. They openly advocated for and instigated the violent overthrow of slavery, which is why they admired John Brown; they had high hopes that Brown was the man who would bring slavery to an end, and they would help him do it. “I am always ready to invest money in treason,” Higginson would write to Brown in 1857.

Theodore Parker was an associate of Ralph Waldo Emerson and one of the first members of the so-called Transcendental Club. Like Emerson, he preached on the divinity of Nature. Unlike Emerson, Parker refused to resign from the ministry when his Transcendentalism upset the Unitarian hierarchy; “I preach abundant heresies,” he proudly proclaimed.

After the Fugitive Slave Law was passed, Parker, already a committed abolitionist, ramped up his radicalism. He openly preached against the new law, was involved in the Underground Railroad, and led attempts to free captured runaway slaves in Boston. Because of his efforts in the war on slavery, Emerson would call Parker a “standard-bearer of liberty.”

Thomas Wentworth Higginson was a Worcester minister whose connections with the Concord literati ran deep. He became a Transcendentalist because of Emerson, and an abolitionist because of Parker; he would comment on the immense influence both men had on his style of radical Unitarianism. He often lectured in Concord and became friends with both Emerson and Thoreau. He married Ellery Channing’s sister, Mary, and was a good friend to Margaret Fuller and her siblings.

Concord Town Hall

| Photo by Richard SmithFrom 1857 to 1859 the Six were constantly funneling money and weapons to Brown. All six of them would be privy to, and supportive of, his raid on the Harpers Ferry arsenal; by October 1859 they had given Brown at least $2000, and he’d collected 200 Sharp’s rifles and 1000 pikes that he hoped to use to arm slaves. But the raid was a failure; most of Brown’s 21 men were killed or captured, while Brown himself would be hanged by the State of Virginia for murder and inciting a slave rebellion.

By the time of Brown’s execution in December 1859, Theodore Parker was in Italy, desperately hoping to recover from the tuberculosis that would kill him on May 10, 1860. Only Higginson would neither deny his involvement with Brown, like Gerritt Smith, or flee the country for Canada, like Sanborn, Howe, and Stearns. Instead, Higginson remained in Worcester and dared authorities to come and get him. They never did.

Higginson would continue his own anti-slavery work by joining the Union Army in 1862 and becoming the Colonel of First South Carolina Volunteers, one of the first all-black Union regiments to fight in the Civil War.

The Secret Six saw the fight against slavery as a revolution, and they viewed John Brown as no different from the men who fought at Lexington and Concord in 1775. After many decades of compromise and appeasement with the slaveholding South, these men believed that drastic actions like Brown’s were needed to free the enslaved millions. While Brown’s attempt at Harpers Ferry failed, his raid was the match that lit the fuse toward civil war, a war that ultimately freed almost 4 million African Americans.

While Brown’s raid may be regarded as insane or foolish, he was a man who put his convictions into action, a man willing to die for the anti-slavery cause. Henry Thoreau called Brown a “transcendentalist above all.” To him, Brown was living out the moral imperative, the transcendental ideal, fighting and dying for the notion that all men are created equal.