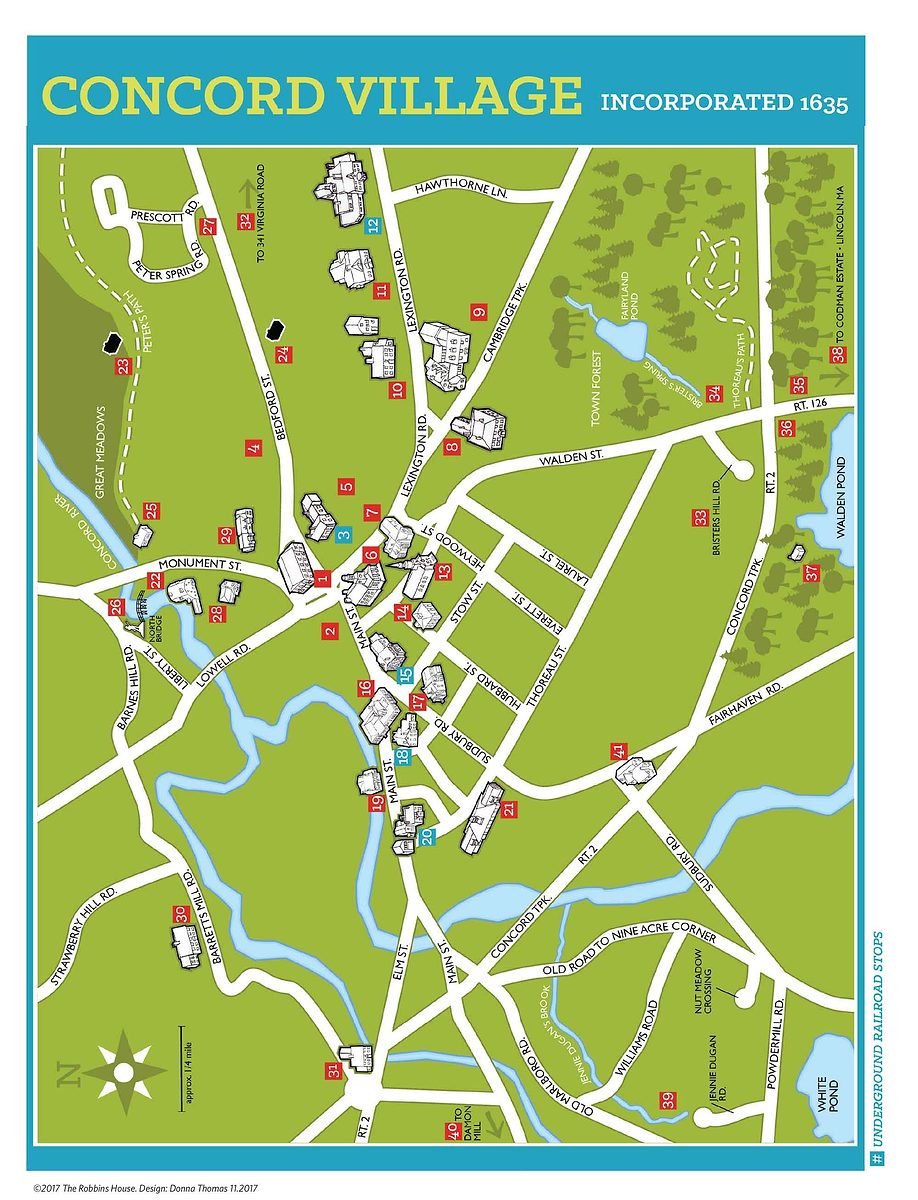

The Robbins House – Concord’s African American History started with a map. Local resident Maria Madison, PhD, who would go on to co-found the the nonprofit organization, The Robbins House Inc., noticed streets in Concord named after early Black residents such as Bristers Hill (33), Peter Spring (27), and Jennie Dugan (39) Roads. Who were these people? Dr. Madison and a few other Concord METCO (Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity) family friends created a map of Concord’s African American history so that students of color from Boston and Concord could see their own history reflected in this storied town. When the Robbins House, a residence which occupied two locations (23 & 24) from 1823-2007, was threatened with demolition, The Robbins House nonprofit was formed to save, move, and restore the building as a center for telling Concord’s lesser-known Black history.

Concord was a slave town well before it became a hotbed of antislavery activism. From 1725 to 1776, about 30 Concord men of high status each had the wealth to purchase and enslave one to two men, women, and/or children. “Servants for life” were forced to provide the critical household and outdoor labor that enabled public officials, doctors, lawyers, gentlemen farmers, and even ministers to pursue the activities that created their wealth. A room on the top floor of the Old Manse (28) was reserved for slaves and later servants. On April 19, 1775, Rev. William Emerson’s enslaved man “Frank” – later known as Francis Benson – rushed into the home with word that the Regulars were coming.

In 1780, Massachusetts adopted a new constitution with a preamble declaring that “all men are born free and equal.” However, it took several years and court cases brought by Blacks suing for their freedom before slavery was overturned in the courts in 1783. Still, emancipation was gradual, with slavery lingering until about 1800.

Notice that sites 23, 34, 35, 36, and 39 on the Concord Village map are all located on the margins of town. These are the homesites of Concord’s earliest free Black residents who forged livelihoods following slavery: Caesar Robbins, a Patriot, and John Jack, whose Burying Ground gravestone bears an early antislavery epitaph (5), both lived on depleted farmland overlooking the Great Meadows. As immortalized in Thoreau’s Walden, Patriot Brister Freeman (34), Cato Ingraham (35), and Zilpha White (36) struggled on the infertile soil of Walden Woods. Brister Freeman left his signature in the landscape with a ditch fence still visible in the town forest. Thomas Dugan (39), who escaped slavery in Virginia, introduced the rye cradle and new techniques for grafting apple trees to Concord farmers.

By the mid-1800s, Caesar Robbins’s grandson John Garrison, Jr. achieved a steady income as Concord’s Town House caretaker and built a Victorian house near the town center (29). Several residents of the Robbins House (23) signed civil rights petitions, and John’s sister, Ellen G. Jackson, legally tested the 1866 Civil Rights Bill in Baltimore. For much more of Concord’s Black history, download the complete map description at robbinshouse.org.