6 | Thoreau-ly Misrepresented

Perhaps none of Concord’s authors has been judged and characterized to the extent that Henry David Thoreau has, and interestingly, the claims about him span a complete spectrum. Upon their first visit to Walden, visitors are often surprised that Thoreau wasn’t the absolute mad-haired, isolated hermit they often assumed him to be, whereas those more familiar with Thoreau will often take the other extreme view, that since Henry would walk into Concord and go “home” to mom’s cooking and laundering skills his whole living in the woods experiment was actually a fraud. The truth lies somewhere in the middle; Thoreau wasn’t isolated, but he WAS often alone, and while he did grow his own crops and cook them, he sometimes enjoyed meals at home with his family.

And what of the notion that Thoreau was “squatting” on the land near Walden Pond on which he built his cabin? While he does make light of this in a pun (“I put no manure whatever on this land, not being the owner, but merely a squatter…”) the truth is that Ralph Waldo Emerson was perfectly aware of and even encouraging of his odd tenant that took up residence — with permission — on the Emerson family wood lot. Thoreau paid no rent, but he was expected to clear brush and brambles, which he did so he could grow his beans.

7 | That Time Thoreau Went to Jail and Emerson Didn’t Visit

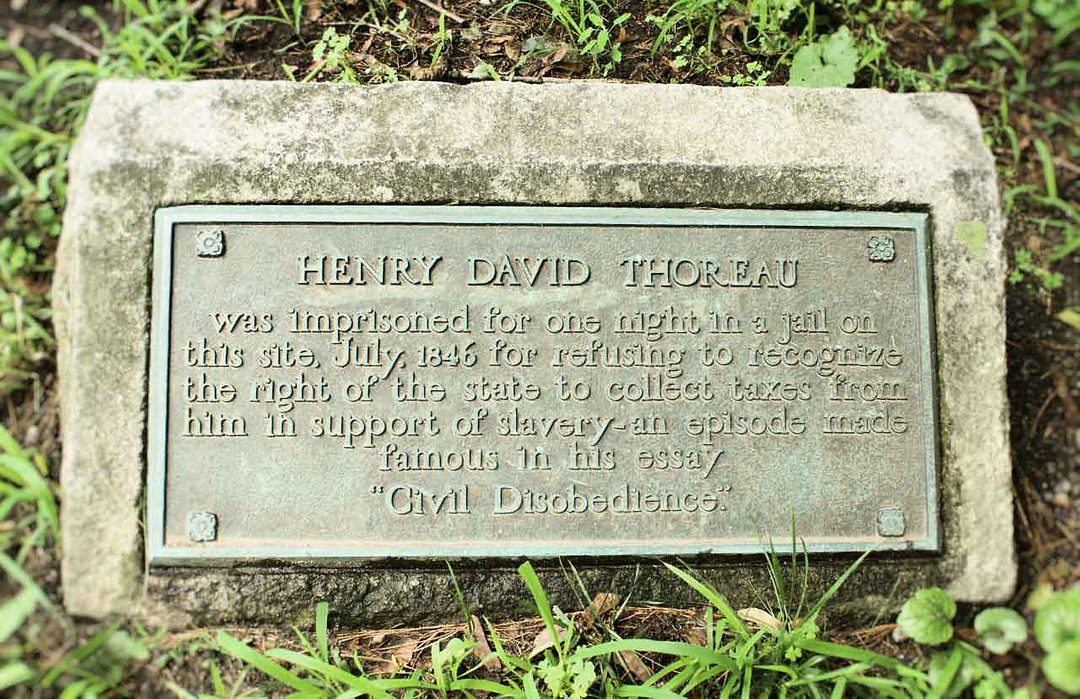

The story is well known: in July of 1846, while walking into Concord from his Walden Pond house to have a shoe repaired, Henry Thoreau was stopped by constable Sam Staples and asked to pay his poll tax for the year. When Thoreau refused, as a protest against the Mexican War, Staples arrested Thoreau and put him in the Concord jail.

Thoreau would spend one night in the Concord jail. He would be released the next morning because the tax was paid — not by him, but by someone else, probably his aunt, Maria Thoreau.

There is a story that claims that Ralph Waldo Emerson visited Thoreau while he was in jail. When he saw his young friend behind bars he asked, “Henry why are you in jail?” Thoreau cheekily replied, “Waldo, why are you NOT in jail?” A great story — but it NEVER happened. In fact, Emerson knew nothing of Thoreau’s arrest until the next day, after Thoreau had been released.

So where does that story come from? Well, in a play called “The Night Thoreau Spent in Jail” by Robert E. Lee and Jerome Lawrence, Ralph Waldo Emerson does indeed visit Thoreau in jail, and the famous exchange between the two men takes place. First produced in 1970, that scene (taking a big dose of literary license) has been quoted as gospel ever since.

8 | A Naughty Nothingburger

Claim: Lidian Emerson and Henry David Thoreau had an affair. This one’s easy to debunk, though endlessly amusing in its persistence.

After Thoreau left his cabin on the pond, but before he completed and published Walden, he moved in with the Emersons for a time. Waldo was leaving on an extended lecture circuit of England and thought it a win-win for everyone if Lidian and the children had an extra pair of hands around to help with everything from tutoring to splitting firewood during his absence. The arrangement was hardly scandalous and would probably never have become a thing but for a 2007 historical novel called American Bloomsbury in which, among other egregious insinuations, one is left with the impossibly hilarious idea that Lidian and Henry briefly danced a dalliance. But the truth isn’t nearly so salacious; while Thoreau and Lidian had great affection for each other, it was more of an older sister/younger brother relationship.

Louisa May Alcott’s grave and U.S. veteran marker honoring her service

| ©Richard Smith9 | Louisa, Feeling Testy

There is no disputing that Louisa May Alcott was the first woman to register to vote in Concord, Massachusetts in July 1879. This oft-repeated tall tale starts with how she registered to vote.

On August 23, 1879, an article in the Women’s Journal stated Louisa needed to pay her taxes before being allowed to register to vote, describing a back and forth banter between the assessor and Louisa that included snarky remarks and comical looks. Louisa refutes the August 23 story with her factual version in the October 11, 1879, Women’s Journal clearly stating the previous story was told by gossips. In her own words Louisa writes that she “showed my bill, was asked where I was born, age and profession; requested to read a few words from the Constitution to prove that I could read, to sign my name to the paper to prove that I could write, and that was all.” The gentlemen were courteous and made registering to vote as easy as possible.

As for the literacy test Louisa was required to take, a number of states ratified them after the 15th amendment with the intent of keeping blacks from registering to vote.

10 | March to War?

Anyone familiar with the story of Little Women probably remembers the touching mayhem that ensued when Mr. March, who had been away serving as a chaplain during the Civil War, sends the entire family into spasms of delight by returning home unannounced on Christmas day.

While the real-life Alcotts as a whole were staunch abolitionists who participated in the Underground Railroad, it was Louisa and not her father who was able to serve her country as a nurse during the Civil War, beginning in December 1862.

For those visitors more familiar with the March family than the Alcotts, this sometimes confuses them upon arriving in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery and spying a Civil War Veteran marker next to Louisa’s grave. Occasionally, someone will even feel compelled to move the marker thinking it belongs next to Bronson, or the Alcott family marker, but its true home is honoring LMA.

Louisa served but six weeks as a nurse before she was struck down with typhoid pneumonia and returned to Concord, but the severity of the illness profoundly affected her health the rest of her not-so-long life. The diminutive and endlessly readable book, Hospital Sketches, is a fictionalized account of her time at the hospital in Georgetown and, we feel, one of Louisa’s best works.