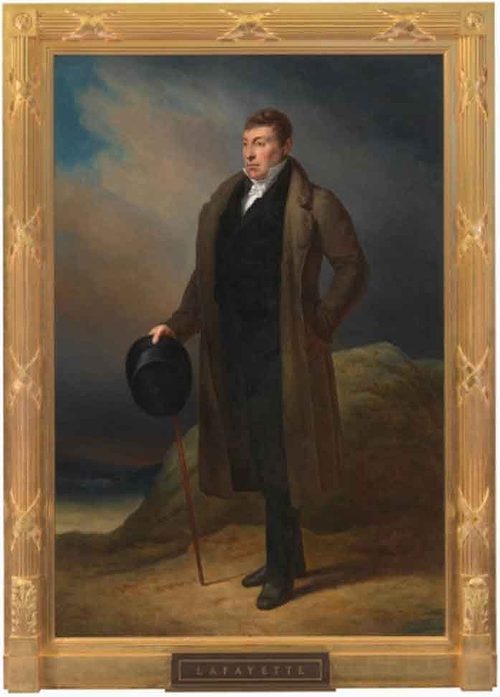

Concord, Massachusetts, is home to two important revolutions: a military one starting on April 19, 1775, and a moral, intellectual, and ideological one, epitomized more than half a century later by the Transcendentalist movement and its staunch support for the abolition of those enslaved in America. Few heroes in American history resonate so strongly with both of these movements as the iconic Frenchman, the Marquis de Lafayette.

Lafayette and the Fight for American Independence

At age 19, influenced by the ideals surrounding the discoveries of the Western Enlightenment, Lafayette sailed to North America to help establish an independent nation that would guarantee the equal protection of the natural rights of individuals under the law. He befriended George Washington and was quickly elevated to the rank of Major General in 1777. Lafayette bled for America at Brandywine and served at Barren Hill, Monmouth, and Newport.He remained a staunch ally to the emerging United States and a trusted friend of Washington. His influence was instrumental in securing military support from France, which would ultimately lead to the victorious siege at Yorktown, Virginia, in October of 1781.

In 1824, Lafayette was invited on a special tour of the United States by President Monroe and Congress in honor of the 50th anniversary of the American Revolution. From August 1824 to September 1825, he was the “Nation’s Guest,1” traveling more than 5,000 miles across the then 24-state union. As the last surviving Major General from the Revolution, the charismatic Lafayette was greeted with much pomp and circumstance wherever he went. His presence on American soil provided much-needed common ground between Americans amidst the deep partisan divisions polarizing the nation during the 1824 U.S. presidential election.

Americans looked to Lafayette for clues, recognition, and reassurance of the success of the American Experiment. Lafayette, the close friend of Washington, consolidated the belief among Americans that the federal republican form of government adopted in this country was unique and worthy of pride. His visit led to an increased sense of national awareness, to a renewed interest in the conflict leading to national independence, and to a greater understanding that the ideals of the American Revolution ought to be preserved for future generations.

Stopping in Concord on September 2, 1824, on his way back from Boston to New York City, Lafayette highlighted the importance of the shots fired at Concord in April 1775: “It was the alarm gun to all Europe, or as I may say, the whole world. For it was the signal gun, which summoned all the world to assert their rights and become free.” His military service was honored by Concord residents, who claimed that “From the 19th of April 1775, here noted in blood, to a memorable day in Yorktown, your heart and your sword were with us.” An arch was erected in the town to welcome Lafayette. It bore the inscription, “In 1775 People of Concord met the enemies of liberty: In 1824, they welcome the bold asserter of the Rights of Man, Lafayette.” 2

Jacques Nicholas Bellin, Carte de la Guyane, 1757

Lafayette – an Inspiration to Human Rights Advocates

Lafayette was a lifelong champion of universal human rights and a staunch abolitionist. He consistently advanced this agenda, as he believed it would benefit the national interest. European philosophers such as Diderot and d’Alembert (1750s-1760s)3, Condorcet (1781)4, and Abbé Grégoire (1815)5 sought to explore the complex ways in which slavery affected enslaved persons. They laid out analyses combining philosophical and moral components to offer a path for ending slavery successfully.

In the United States, Northern abolitionist societies increasingly advocated for the gradual emancipation of enslaved people. Legislation was passed in Pennsylvania (1780) and New York (1799) to promote the idea.6 The Pennsylvania Abolition Society, chartered in 1775, changed its name in the 1780s to reflect this new consideration for “improving the condition of the African Race.”7 This position highlighted the emphasis on ending slavery while ensuring that any abolitionist agenda would lead to the long-term successful insertion of newly freed men and women into society. Many like Lafayette embraced the idea of exploring the lasting damage caused by a lifelong condition of bondage and that slaves needed to be “duly prepared for the rational enjoyment of freedom.”8

Lafayette’s intellectual proximity with these circles led him to conceive of the Cayenne Experiments. In a letter dated February 5, 1783, Lafayette challenged George Washington to address the dilemma of slavery in a society founded on universal human rights and invited his friend to join him in an experiment that would be “greatly beneficial for the Black part of mankind.”9 Unable to obtain the support of Washington, Lafayette proceeded in 1785 with his plan in the French colony of Guiana (now French Guiana). The experiment focused on ameliorating the conditions of bondage on the plantation by eliminating any forms of corporal punishment, enacting laws to prohibit the usage of tools most associated with the violent treatment of enslaved workers, and by encouraging a sense of collective identity.

Sentinel and Democrat (Burlington, Vermont, Friday, September 17, 1824)

Bridging Concord’s Two Revolutions

When Lafayette visited in 1824, the debate around slavery was just as hotly contested in Concord as it was nationally, when The Missouri Compromise of 1820 established Missouri as a slave state, balanced by the free state of Maine. Lafayette consistently laid out a compelling link between the American fight for freedom and the plight of the enslaved in this country. And while Lafayette would never work alongside Emerson, Thoreau, or the Concord Alcotts, his words and his passionate support for universal human rights would resonate with the generation that followed his momentous visit to Concord and further encourage them over the next several decades. His much-celebrated visit in 1824 would serve as a bridge between the ideals of the American Revolution and the foundational philosophies espoused by the Transcendentalists to come.

Sources

1 Connecticut Gazette (New London, Connecticut, September 22, 1824). 2 Sentinel and Democrat (Burlington, Vermont, September 17, 1824). 3 Diderot, d’Alembert, Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, par une société de gens de lettres, 28 vols (Paris, France, 1751). 4 M. Schwartz (Condorcet), Réflexions sur l’esclavage des Nègres (Neufchâtel, 1781), 44p. 5 Grégoire, Henry, De la Traite et de l’esclavage des noirs et des blancs (Adrien Egron: Paris, France, 1815), 40p. 6 https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/gradual-abolition-act-of-1780/, http://www.archives.nysed.gov/education/act-gradual-abolition-slavery-1799. 7 Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, Five Years’ abstract of Transactions of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery the relief of free negroes unlawfully held in bondage, and for improving the condition of the African Race (Merrihew and Thompson’s: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1853). 8 National Journal (Washington, D.C., May 12, 1825), 1. 9 “To George Washington from Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette, 5 February 1783,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10575.