In the early spring of 1862, as the first buds began to appear, two men made their way along Main Street. Concord knew this pair well; over the last twenty years, these “knights of the umbrella and bundle”1 had rambled together from the Walden Woods to Montreal, from Cape Cod to the Catskills.

Henry Thoreau had been the more vigorous of the two, but today the poet Ellery Channing offered Henry an arm to lean on as he paused to catch his breath. His tuberculosis was growing worse, and his faithful friend Ellery had come to walk this familiar path with him for what might be the last time.

Ellery Channing

| Courtesy Concord Free Public LibraryEllery Channing’s great gift was friendship. His Concord compatriots stood by him through good times and bad. There were plenty of bad times, often of Ellery’s own making, but his conversation flowed with thoughtful insights, rowdy humor, and disarming candor. His writing was never more than passable—and he vehemently refused any editor’s efforts to improve it—but the writers in his circle swore that his companionship fueled their creativity.

So why did biographer Robert Hudspeth call him “the most lonely Transcendentalist”?2 What secret alienation did he conceal beneath his engaging manner and ready wit?

His life had an auspicious start. He was born in Boston in 1817, the son of the dean of the Harvard medical faculty. He was named after his uncle, William Ellery Channing, an influential Unitarian clergyman whom Waldo Emerson called the “Star of the American Church,”3 and the family called him “Ellery” to avoid confusion with his celebrated namesake.

The path to wealth and comfort seemed laid out before him, but when he was only five, his mother died. The traumatic loss that haunted the child grew into a sense of betrayal in the man, and he condemned all the solid Yankee values that his family cherished—progress, prosperity, piety—often to his own detriment.

He grew up brilliant but unfocused. He enrolled at Harvard but dropped out after fourteen weeks. On his own, he read Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, and Goethe and tried his hand at writing, even getting a few poems published in Boston periodicals.

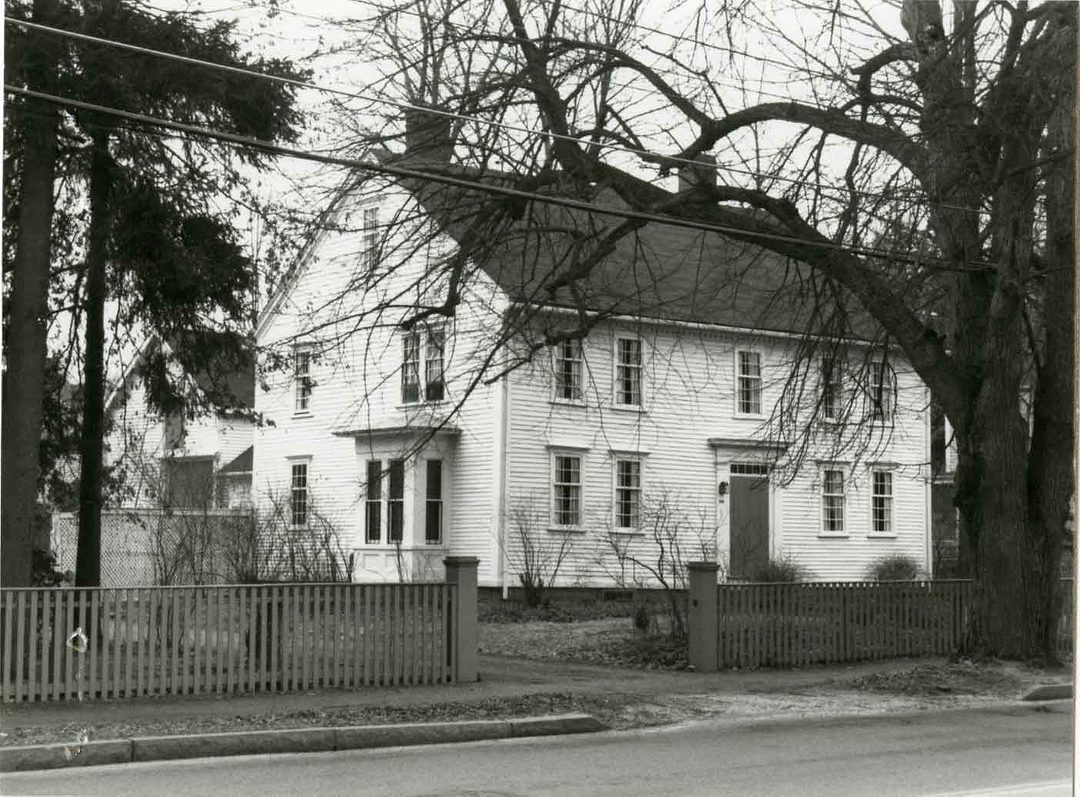

The Frank Sanborn house where Channing spent the last years of his life

| Courtesy Concord Free Public LibraryBut for him, Boston embodied the bourgeois life he despised, so at age 22 he headed west. He ended up in Cincinnati, writing poetry and doing occasional newspaper work. A school friend sent a bundle of Ellery’s poems to Waldo Emerson, who was preparing to launch a new magazine, The Dial.

Waldo took note of Ellery’s shortcomings—“[He] defies a little too disdainfully his dictionary and logic”—but he was won over by Ellery’s “highly poetical temperament and a sunny sweetness of thought and feeling,”4 and published his poems in almost every issue of The Dial.

In Cincinnati in 1841, Ellery met Ellen Kilshaw Fuller, another young Massachusetts native trying her luck in Ohio. They were married less than two months later. Emerson urged his protégé to come with his new bride to Massachusetts, and this they did in 1842.

They found Concord was already home to a thriving writers’ colony. Henry Thoreau and Margaret Fuller were frequent visitors at Waldo’s house, with Bronson Alcott and Nathaniel Hawthorne both living nearby. Ellery took a seat at the Transcendentalists’ table, not just as a contributor to The Dial, but now as brother-in-law to its editor, Margaret Fuller.

Margaret found Ellery brilliant and witty, but she worried that a scribbler of middling poetry would be a poor breadwinner for her sister Ellen. He didn’t boost her confidence when he came early to Concord to prepare for his wife’s arrival, only to slip away for a chaste holiday with Caroline Sturgis, another Dial poet with whom he had had a flirtation several years before. When Ellen arrived, she seemed to take her husband’s truancy in stride, but his career as a family man was off to a rocky start.

The contentment that eluded him at home he sought in nature, and in Concord he found the pastoral Eden he had gone west to pursue. He spent his days traipsing its woods and rivers, and his evenings composing hymns to its blooms and breezes:

“A thousand flowers enchant the gale

With perfume sweet as love’s first kiss,

And odors in the landscape sail,

And charm the sense with sudden bliss.”5

His rebellious spirit abandoned him when he put pen to paper; conforming to rules of rhyme and meter sapped his nature writing of its passion. But when he left his desk and plunged into nature, he showed an uninhibited joy that endeared him to Bronson Alcott and Waldo Emerson, who proclaimed him “Professor in the Art of Walking.”6 Even the famously aloof Nathaniel Hawthorne found Ellery a welcome companion for “skating, rowing, smoking, or lounging.”7

Of all his Concord friends, Henry Thoreau was the closest. Soon after they met in 1842, they began daydreaming about building a writers’ retreat at Walden Pond, and in March of 1845, Henry got a letter from Ellery (who was in New York dabbling in journalism again) saying “build yourself a hut, and there begin the grand process of devouring yourself alive.”8 Ellery got himself fired in time to help Henry build his Walden house that summer, and even shared Henry’s cramped quarters for two weeks that August.

Henry embodied Ellery’s ideal: A man who, unencumbered by marriage or mortgage, spent his days searching for truth and beauty and distilling them into immortal literature. He sang Henry’s praises in verse:

“A Lake,—the blue-eyed Walden . . .

. . . has added to its charm,

For one attracted to its pleasant edge,

Has built himself a little Hermitage,

Where with much piety he passes life.”9

Another Channing scholar, Frederick McGill, noted that “each was an eccentric individualist who took obvious delight in rubbing against the grain of the town’s expectations. Neither would work steadily; neither paid much attention to his family.”10 Ellery’s wife Ellen bore his frequent absences and his temperamental presence until 1853, when she took their children and moved out, leaving him to keep bachelor’s hall and spend his days sauntering with his friend, which he did until consumption left Henry too weak for outdoor adventures.

During Henry’s final illness in 1862, Ellery was daily at Henry’s bedside and took him for walks when he felt well enough. When his life ended on May 6, Ellery composed a hymn that was sung at his funeral, and later included it in a reverent biography that Ellery published in 1873.

“As long as Walden’s waters roll . . .

His perfect trust shall keep the fire,

His glorious peace disarm all loss!”11

Ellery outlived his companions. Hawthorne died in 1864, followed by Emerson and Alcott in the 1880s. Their camaraderie had been his great life’s work, and without them he retreated into a sad and solitary old age—truly the most lonely Transcendentalist—until his death in 1901.

His legacy is this: His genius was the oil that consumed itself to make Concord’s literary lights burn a little brighter.

1Laura Dassow Walls, Henry David Thoreau: A Life, University of Chicago Press, 2017. 2Robert Hudspeth, Ellery Channing, Twayne Publishers, 1973. 3Carlos Baker, Emerson Among the Eccentrics, Viking, 1996. 4Ibid. 5The Dial, Vol. III, No. 2, October 1842. 6Walls, op. cit. 7Hudspeth, op. cit. 8Megan Marshall, Margaret Fuller: A New American Life, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013. 9W. Ellery Channing, Poems: Second Series, J. Munroe and Co., 1847. 10Frederick McGill, Channing of Concord, Rutgers University Press, 1967. 11W. Ellery Channing, Thoreau: the poet-naturalist: With memorial verses, Roberts Brothers, 1873.