One May morning in 1775, two men set out from Cambridge, bound for Lexington and Concord. The older one, Ralph Earl, was just shy of his twenty-fourth birthday, but was already an artist of some note. He lived in New Haven, Connecticut, but he had come to Boston to paint portraits.

One May morning in 1775, two men set out from Cambridge, bound for Lexington and Concord. The older one, Ralph Earl, was just shy of his twenty-fourth birthday, but was already an artist of some note. He lived in New Haven, Connecticut, but he had come to Boston to paint portraits.

His companion, Amos Doolittle, had recently finished his apprenticeship to a silversmith in Cheshire, Connecticut, and had set up shop as a bookseller in New Haven, trying to generate a little income while he established himself as an engraver and printer. His career was sidelined on April 21, 1775, when a messenger arrived in New Haven with the news that war had begun between the American colonies and Britain.

Amos Doolittle, lithograph by Samuel Perkins Gilmore

Doolittle was a patriot and a militiaman, so when his captain—a prosperous sea trader named Benedict Arnold—ordered his unit to join the provincials besieging the British troops in Boston, he shouldered his musket and joined the march. Arriving there on April 29, he learned that like most sieges, this one involved a lot of waiting. But he did encounter Ralph Earl—they had probably met in New Haven—and together they planned their expedition to Lexington and Concord.

The battles here on April 19 were electrifying news, and Doolittle knew that being the first to market pictures of the conflict would get his fledgling engraving business off the ground (and at the same time, rally support for the patriot cause, as Paul Revere’s 1770 engraving of the Boston Massacre had done).

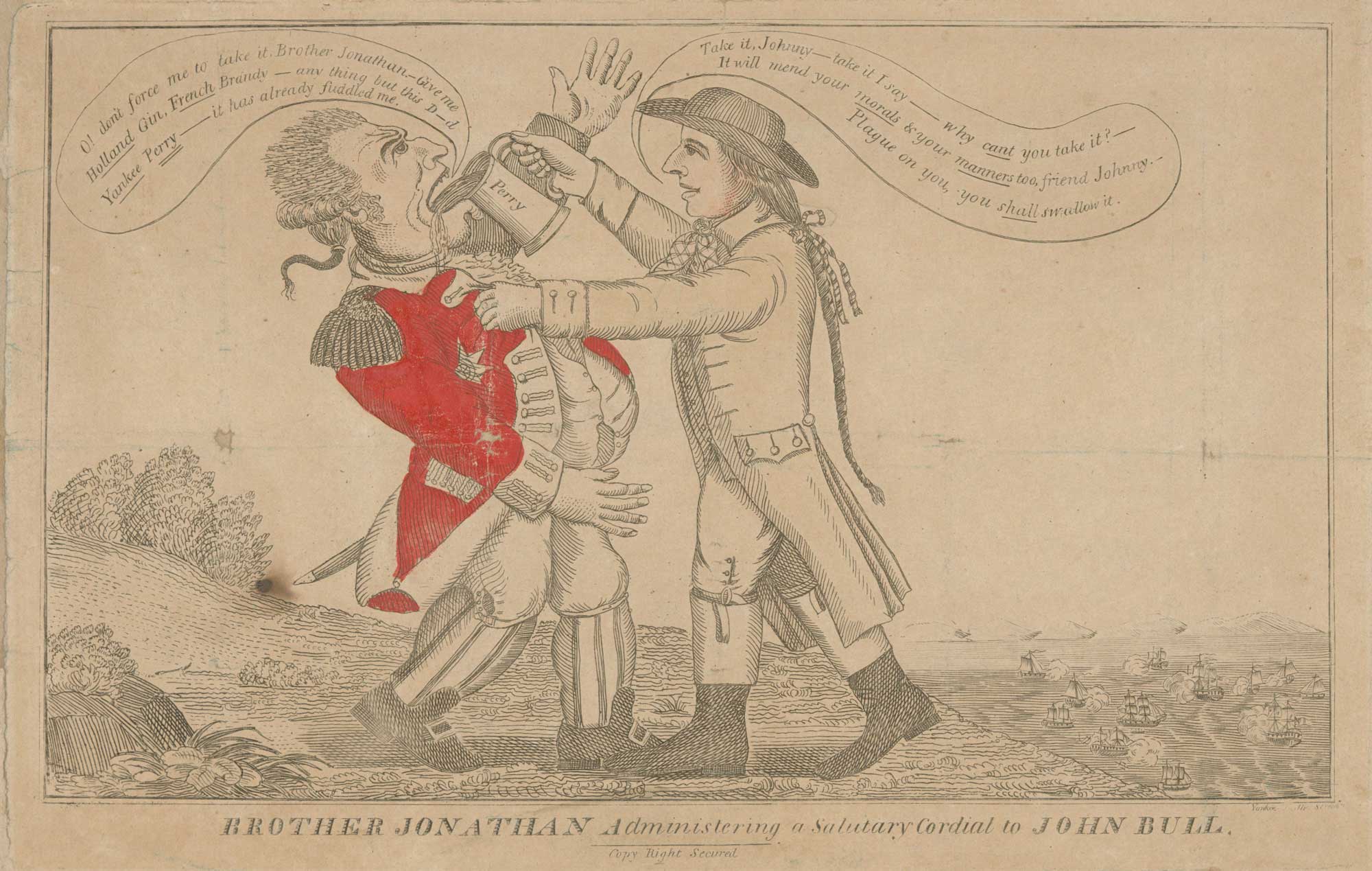

“Brother Jonathan Administering a Salutory Cordial to John Bull” by Amos Doolittle, 1813

Doolittle was a skilled craftsman, but had no training as an artist. That’s where Ralph Earl came in. Earl would sketch the battle sites, and Doolittle would copy Earl’s drawings onto engraving plates. According to Doolittle’s colleague John Warner Barber1, Doolittle acted as Earl’s model, assuming various martial stances as Earl added figures to his battlefield scenes. Barber affirmed that “These plates, though crude in execution . . . give a faithful representation of the houses, etc., as they appeared at that time.”2

Doolittle published his set of four engravings (two of Lexington, two of Concord) later that year, priced at six shillings plain, eight shillings hand-colored. As printing historian Donald C. O’Brien wrote, “people pasted [Doolittle’s prints] to their parlor or outhouse walls; shop owners used them as posters, and town selectmen tacked them up on public billboards. Such ephemeral usage could account for their scarcity today. Once their message was no longer a priority, they were taken down and the paper used for other purposes.”3

In time, people realized the importance of the visual record that Doolittle created, and new limited-edition versions of the prints were produced in 1885, 1902, 1960, and 1975. The 1902 edition, published by Boston bookseller Charles Eliot Goodspeed, is often seen in modern museums and private collections.

Returning to civilian life in New Haven, Doolittle kept a shop on the corner of the Yale College yard. The war with England had caused a shortage of money and goods, so he cobbled together a living by doing a little bit of everything. He printed designs on fabric, painted signs, worked in silver, and even made metal buttons.

His proximity to Yale brought him a steady flow of small printing jobs. He began engraving Yale diplomas in the 1780s and continued to do so for at least thirty years. His work brought him to the attention of Benjamin Silliman, Yale’s first professor of chemistry, and when Silliman launched The American Journal of Science in 1818, he turned to Doolittle to provide maps as well as images to illustrate concepts in mechanics, geology, and astronomy. Over the next decade he would provide at least sixty plates for Silliman’s Journal. (As with his Lexington and Concord prints, Doolittle transferred to printing plates images that had been drawn by Silliman or others.)

In the early years of American independence, the new nation had to learn how to manage things like currency and defense on its own. After 1793, coins were minted by the federal government, but paper money was issued by banks. The Washington Bank of Westerly, Rhode Island had Doolittle engrave plates for bank notes in various denominations. Of course, to get a contract to print money, Doolittle had to be “above suspicion,” and it seems he was, as in 1797 New Haven entrusted him with the job of tax assessor.4

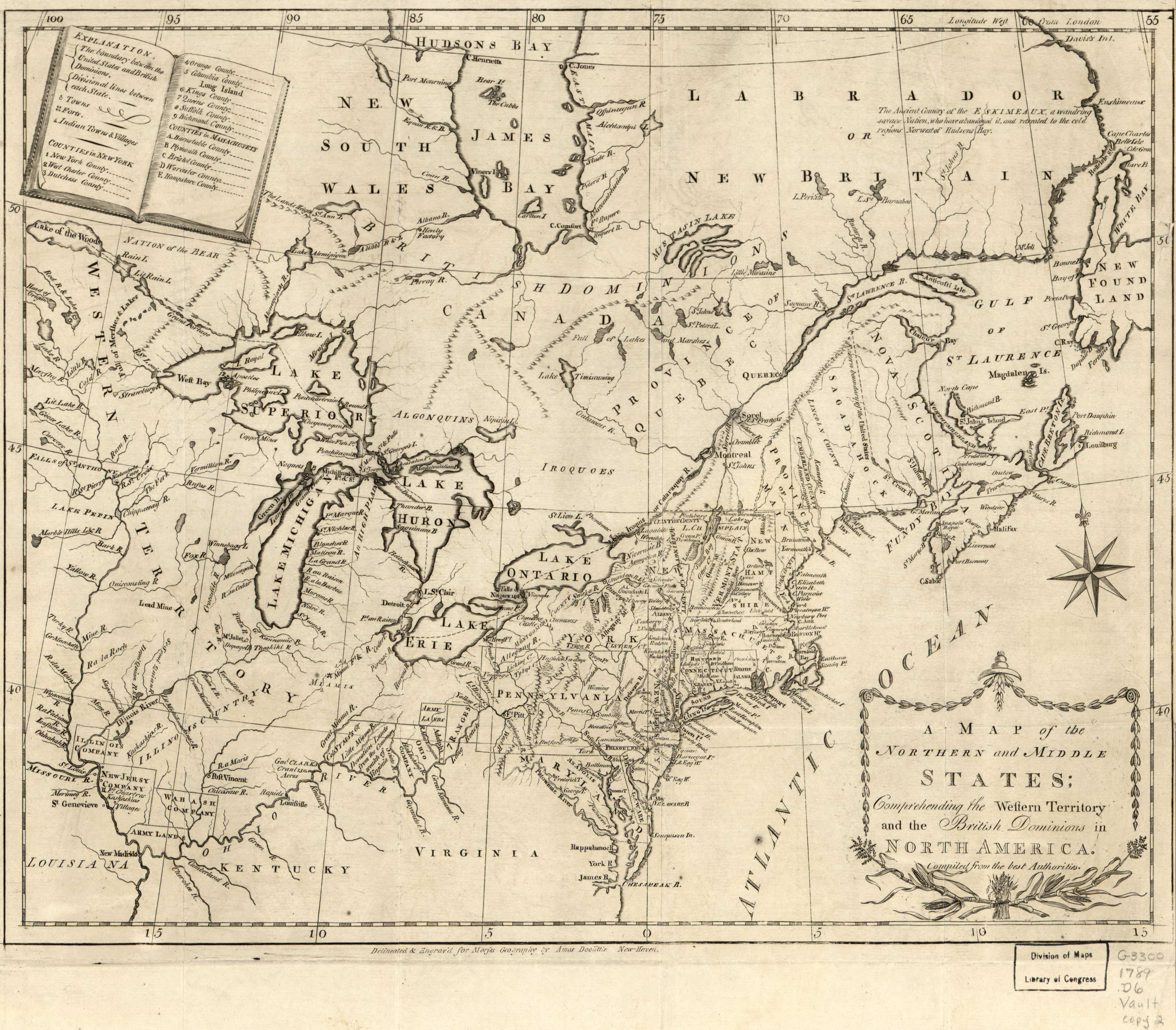

“A Map of the Northern and Middle States” engraved by Amos Doolittle, 1789

When the U.S. Congress passed the Militia Act in 1792, states needed training manuals for their militias. Publisher Isaiah Thomas adapted the manual written by Baron Friedrich von Steuben during the American Revolution and published a new edition in 1797 with illustrations engraved by Doolittle.

As the new nation of America grew, its citizens wanted to examine how it was growing. Yale President Ezra Stiles observed in 1794 that most New Englanders “read Geography with avidity and Improvement,”5 and many of them were buying maps produced by Amos Doolittle. In 1789, he engraved “A Map of the Northern and Middle States” for The American Geography by Jedediah Morse. Over the next seven years, he would engrave twenty-five more plates for editions of Morse’s Geography Made Easy. 148 Doolittle maps have been documented in dozens of books from the period.

Under British rule, Americans had to import Bibles from England, as colonial printers were forbidden to produce them. Once American publishers were free to issue Bibles, Doolittle’s services were in demand. He engraved fifty or more plates of religious subjects. He and a partner, Simeon Jocelin, also published a hymn book, The Chorister’s Companion. A few years later, he branched out into secular music, engraving pages for The Select Songster.

Through his prolific and varied career, Amos Doolittle never stopped using his professional skills to stir patriotic sentiments in his fellow citizens, as he had done with his Lexington and Concord prints. During the War of 1812, he produced broadsides celebrating American victories over the British Navy, notably “Brother Jonathan Administering a Salutory Cordial to John Bull,” showing American Captain Oliver Hazard Perry forcing his British opponent, Captain Robert Barclay, to drink from a tankard of perry, the name of a liqueur but also a pun on Perry’s name.

Although not himself a statesman or a scholar, Doolittle made the work of statemen and scholars available to thousands of Americans. When he died in 1832 at age seventy-seven, Benjamin Silliman wrote in The American Journal of Science, “Our venerable old engraver, Mr. Doolittle, has descended to the tomb, nor are we willing that his name should float away on the tide of time . . . [He] was the American patriarch of the art; an amiable and worthy man.”6

NOTES 1 A copy of John Warner Barber’s 1839 engraving Central Part of Concord, Mass. is in the William Munroe Special Collections at the Concord Free Public Library, and reproductions of it can be seen at many locations around town. 2 Barber, J. W. (1839). Massachusetts Historical Collections . . . Door, Howland & Co. 3 O’Brien, Donald C. (2008). Amos Doolittle: Engraver of the New Republic. Oak Knoll Press. 4 Ibid. 5 Dexter, F.B. (1901). The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles. Charles Scribner’s Sons. 6 Silliman, B. (1832). The American Journal of Science, Vol. 22. Hezekiah Howe & Co.