At the 2022 Thoreau Gathering, Concord was honored with a visit from the legendary Dr. Jane Goodall. She was awarded the Thoreau Prize for Literary Excellence in Nature Writing in recognition of her lifetime dedication to the study, understanding, and protection of non-human animals, nature, and our planet. Discover Concord spoke with her about her work, her thoughts on climate change, and her surprising message of hope for the future.

What about Henry David Thoreau’s work resonates with you?

When I was told I had been chosen to receive the Thoreau Prize for Literary Excellence in Nature Writing, I was very honoured. I have always loved writing, and I was delighted that this gift is being acknowledged, particularly in a place where Thoreau lived and worked. He was not trained as a naturalist, but he was an active field-worker and a first-class observer and note-taker. His writing shows his love of nature and his joy of being alone in nature. I feel a bond with this special man and his work continues to be inspirational for me, and for many young people today.

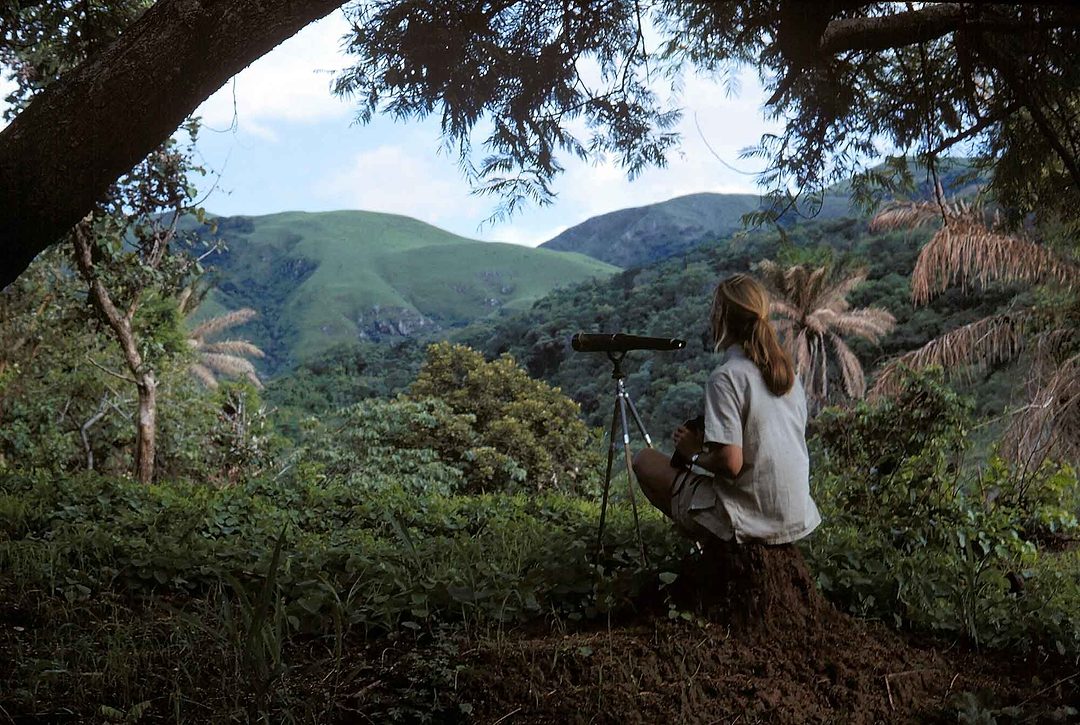

Young researcher Dr. Jane Goodall with baby chimpanzee Flint at Gombe Stream Research Center in Tanzania.

| © Jane Goodall InstituteWhat is it that first drew you to nature? Why have you dedicated your life’s work to protecting non-human animals, nature, and our planet?

I was born loving and being fascinated by all animals. Television had not even been invented when I was growing up. Instead, I watched animals in the garden and everywhere I went, from squirrels and birds to spiders and worms. I also learned from books at the library.

First, I fell in love with Doctor Doolittle and his ability to talk to animals. But at age ten, I found Tarzan of the Apes. That inspired my dream—I will grow up, live with wild animals in Africa, and write books about them. Everyone, except my wonderfully supportive mother, laughed at my dream and told me to focus on something I could achieve – as a girl. But my mother said that if I worked hard and took advantage of all opportunities, and if I did not give up, I would find a way to make my dreams a reality.

My mentor, Louis Leakey, gave me an amazing opportunity in 1961 when I was invited to do field study work with chimpanzees in Gombe, Tanzania. Until 1986, I was learning about chimp behavior and that of other animals in the ecosystem of the forest. When I learned that forests were disappearing across Africa and that chimp numbers were dropping, I decided I had to do something, though I wasn’t sure what. I also learned about the other ways in which we were harming nature; the reckless burning of fossil fuels that release huge amounts of CO2 the polluting of the oceans, the agricultural chemicals harming biodiversity and killing the soil, the huge areas cleared to grow grain for factory farming of animals, the heating of the planet from the production of methane (a greenhouse gas) by the billions of factory farm animals crowded into unbelievably cruel conditions, and the enormous water waste. I became increasingly concerned, as I care passionately about the natural world and the future of our children.

Dr. Jane Goodall and her mother, Vanne, sort specimens in her tent in Gombe Stream Chimpanzee Reserve

| © Jane Goodall InstituteWhat are some of the unexpected lessons you’ve learned through studying chimpanzees in Tanzania for more than 60 years?

The first breakthrough was seeing a chimp (David Greybeard, the first to lose his fear of me) using and making tools to fish for termites. As the other chimps gradually came to trust me, I began to understand their complex social structure. Chimps live in a community of 30 to 50 males, females, adolescents, juveniles, and infants. I learned about close family bonds—offspring continue to travel with their mother after weaning and often spend time with their mother and siblings for life. I was increasingly struck by how like us they are—kissing, embracing, patting in reassurance, swaggering, begging with a palm outstretched. They have very different personalities, and there is a big difference in intelligence between individuals.

Males become alpha in different ways; through aggression, by forming alliances and only confronting a higher-ranking chimp when an ally is present, by sheer persistence, and by continuing to challenge even after being wounded in a fight. Two males competing for dominance (swaggering, hair bristling, waving branches, and trying to look as fierce as they can) sometimes remind me of human politicians.

Dr. Jane Goodall, delivering a message of hope at the 2022 Annual Thoreau Gathering in Concord, Massachusetts.

| © Pierre Chiha PhotographersChimps are territorial, and males patrol their territory, sometimes accompanied by females in estrus. Chimps even attack ‘strangers’ from neighboring communities, typically leaving them to die from their wounds. On one occasion, I witnessed a kind of primitive war—with males of a larger community systematically attacking and killing those of the smaller community except for young females who did not yet have infants (they tried to lead those females back to their own community). It shocked me to learn that there are also instances of infanticide and even, very rarely, cannibalism.

But chimps can also be loving and altruistic. For example, an adult male may adopt an infant whose mother has died. Until three years of age, chimps rely mainly on their mother’s milk to survive. But if the child is older than three, there is hope. If there is an older sibling, the child may be cared for within the family. A long childhood is important as the infant has so much to learn—much like us humans.

More study sites have now proven that chimpanzees have cultures. This idea shocked other scientists when I first suggested it might be true in the late 1960s because I saw how infants learned by observation, imitation, and practice.

My detailed notes of chimp behavior, and the films of chimp behavior taken by filmmaker Hugo van Lawick (who became my husband), gradually convinced scientists to admit that we are not, after all, the only sentient, sapient beings on the planet. Today, animal intelligence is a subject of many studies, and there are also studies of animal personality and emotions.

You speak often about the link between social justice (helping humans) and protecting nature. Why are these two things linked?

When I travelled in Africa to learn about problems faced by chimps—the bushmeat trade, habitat loss, losing a hand or foot that was caught in wire snares set by hunters, wildlife trafficking, mothers shot to steal infants to sell as pets or for circuses—I was also learning about the plight of local communities. Crippling poverty, lack of health and education facilities, and degradation of land from population growth of humans and livestock all resulted in the invasion of wild habitats.

When I flew over Gombe in the late 1980s, which had been part of the equatorial forest belt in the 1960s, I was shocked to see the national park was only a small island of forest surrounded by bare hills! There were more people than the land could support. Farmland was overused and infertile. People who were too poor to buy food elsewhere were struggling to survive. Trees were being cut down to make money from charcoal or timber or to clear more land to grow food for families. That’s when I realized that unless we helped these communities find ways of making a living without destroying their environment, we could not save the chimps, the forests, or anything else.

People, animals, and the environment are all deeply connected. Even in a city, we depend on a healthy ecosystem. Every little creature has a role to play in the tapestry that surrounds us. Each extinction is like a pulled thread—if we allow it to go on, soon that tapestry will be in tatters.

What message do you have for young people? Why do you see them as the hope that will save this planet?

Even back in the late 1980s, I was meeting high school and university students who seemed to have given up hope. Some were angry or depressed. They told me that my generation had compromised their future and there was nothing they could do about it. Indeed, we have been stealing their future (and the resources of their planet) since the industrial revolution.

But there is a window of time during which, if we get together and act, we can slow down climate change and the loss of biodiversity. With a group of just 12 high school students and their friends, we started Roots & Shoots, a Jane Goodall Institute environmental and humanitarian program. The concept is simple. Each group chooses three projects to make the world a better place—for humans, animals, and the environment. The projects they choose depend on their age and their environment. They discuss their projects, work out what they can do, roll up their sleeves, and act. It gets them away from the screens and thinking about the world around them.

Today, we have hundreds of thousands of members from kindergarten through university in 65 countries, and it’s growing. Once these young people see the results of their work and learn that others are also working to make this a better world, they have new hope. That hope inspires them to change the world. It inspires me, too.

A Source of Hope

Dr. Goodall promotes an important message wherever she goes in the world today—live simply, respect individuals, and be concerned about nature and humanity. Her words, actions, and writings serve as a constant source of inspiration and hope for the generation that must now take up the mantle and fight for our collective future. You can be a part of that change too. Learn more about the Jane Goodall Institute and the Roots & Shoots program at:

janegoodall.org

NOTE: The Jane Goodall Institute does not endorse handling, interacting or close proximity to chimpanzees or other wildlife.