When did the American Revolution begin? At the North Bridge on April 19, 1775, with “the shot heard round the world”? In Philadelphia on July 4, 1776, with the Declaration of Independence? John Adams thought the Revolution was over by the time the first guns were fired. It “was effected in the minds and hearts of the people.”

Arguably, that crucial turning-point occurred in Concord two hundred fifty years ago, when on October 11, 1774, delegates from all over Massachusetts, roughly 243 representatives from close to 200 towns, including the District of Maine, gathered in the Congregational meetinghouse (now First Parish) to deal with “the dangerous and alarming situation of public affairs” touched off by Britain’s harsh reaction to the Boston Tea Party. The mother country revoked the colony’s charter, issued in 1691 by William and Mary, and severely curtailed the popular role in government. Towns were prohibited from meeting more than once a year without the Governor’s consent. All judicial officers – judges, juries, and sheriffs – and members of the provincial council were made agents of the Crown. The port of Boston was closed to trade and the seat of government moved to Salem. And although the freeholders of each town could still send representatives to the General Court, the Governor could refuse to call the legislature into session.

That’s what happened in October 1774. The countryside was in uproar, as angry crowds intimidated royal officials into resigning their posts and blocked courts from dispensing justice. Everywhere county conventions sprang up to denounce the new regime and call for a province-wide conclave. In this tense atmosphere Governor Thomas Gage saw no reason to invite still more trouble by bringing the people’s representatives together.

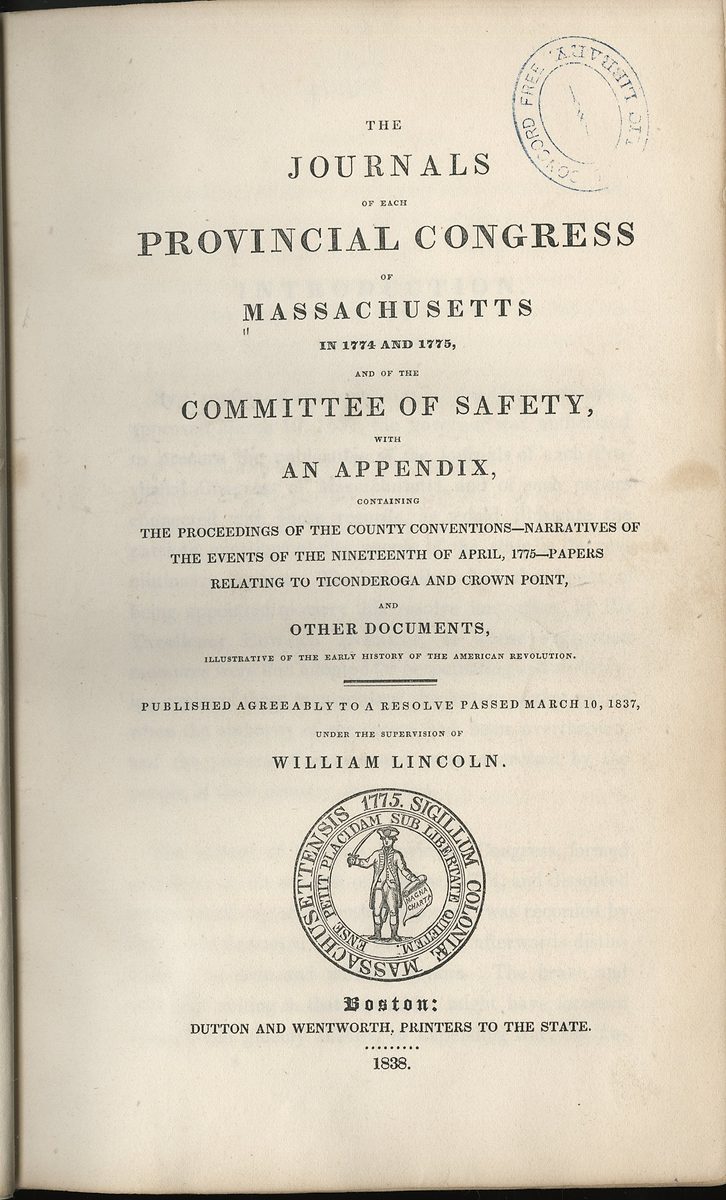

Barred from gathering as an official body in Salem, the assembly reorganized as a provincial council and convened in Concord. The meetinghouse was the venue for formal proceedings; committees met over drinks in Wright Tavern. Over the next eight months sessions would circulate among Cambridge, Concord, and Watertown. The proceedings were guided by such luminaries as John and Samuel Adams, John Hancock, Elbridge Gerry, Dr. Joseph Warren, and Benjamin Lincoln. On this provincial stage, despite professing loyalty to the King, the delegates steadily chipped away at imperial authority, until they had seized the reins of government. First, they claimed the power of the purse and commandeered the taxes collected by the towns. Then they applied the funds to secure the power of the sword. The Congress took control of the militia, amassed arms and ammunition, authorized an army, and established a system to alarm the countryside and foil the King’s men in case of “sudden” maneuvers by “our Enemies.” Without the Provincial Congress there would have been no Patriot victory on April 19.

The Wright Tavern Legacy Trust and Concord250 will commemorate the Provincial Congress, 250 years to the day of its opening session and at the same site, First Parish meetinghouse, with a program of lectures and conversations about popular self-government in Massachusetts and the United States, past, present, and future. Participants will include noted scholars, Massachusetts legislators, teachers and students, and members of the public. For further details see WrightTavern.org/history.