Concord boasts several house museums, but one stands apart as a place of pilgrimage. Filled with authentic Alcott furniture and belongings, Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House, where Little Women was written and set, looks and feels as if the family just stepped out for a moment. The passion exhibited by more than 50,000 people who tour inside the house each year and more than 100,000 who visit the grounds is unsurpassed. Because Little Women has been translated into more than 50 languages, visitors from around the world flock to the site.

Orchard House

| © Trey PowersOrchard House Executive Director, Jan Turnquist, says, “Louisa May Alcott’s legacy is large and powerful because, paradoxically, she so successfully shares the small and vulnerable. She juxtaposes humor and sorrow just as life does. She bares her soul with all its emotion—painful and joyous—and with all its flaws and strengths.”

Turnquist continues, “I’ve had the privilege of witnessing the enormous impact of Alcott and her writing on thousands of Orchard House visitors. They share stories that reveal how Alcott’s works have moved their minds and spirits—even how it has changed their lives. When asked, ‘Why does Louisa so deeply touch readers and forge such a powerful bond, transcending time, place, culture, and even death?’ I answer, because she so profoundly connects with them. Louisa reaches directly from her heart to that of her reader revealing her authentic self, warts and all. The particulars of her story and of visitors’ stories vary but the common denominator is human connection.”

Jan Turnquist

| © Maria PowersStories of connection are as numerous and diverse as Alcott enthusiasts themselves, grounded in the present moment as if Louisa and her family were alive today.

Biographer John Matteson’s rapport with Louisa and her father Bronson resulted in his Pulitzer prize-winning dual biography, Eden’s Outcasts. “I lived my biography of Louisa,” he said. “This period in my life was the ideal preparation for an Alcott scholar. What better biographer of Bronson, a quixotic, education–obsessed man with a verbally gifted daughter, than another quixotic, education–obsessed man with a verbally gifted daughter? I am convinced that writing Eden’s Outcasts made me a better, more attentive father. I also know that my experience as a hands-on dad enabled me to understand Bronson and Louisa with a rare kind of intimacy and familiarity.”

John Matteson

| © Amy T. ZielinskiAuthor Susan Cheever speaks of Orchard House in her 2010 book, Louisa May Alcott: A Personal Biography: “I was thrilled to be in the presence of the real thing, the place where the writing of Little Women occurred. . . as if some alchemy in the wood might pass into my own restless spirit. I couldn’t wait to get home to the book.”

Celebrated photographer, Annie Leibovitz, who was interviewed for Turnquist’s Emmy award-winning documentary, “Orchard House: Home of Little Women” said, “What surprises me so much about the House is that it is really a living house. I’ve never seen a museum like this that has so much character and life.”

Annie Leibovitz

| ©Lone Wolf MediaGreg Eiselein is President of the Louisa May Alcott Society (founded 2005) which, allied with the American Literature Association (ALA), offers Alcott scholars and others an opportunity to present papers on Alcott at literary conferences. Eiselein cites his particular interest in Louisa’s sense of humor despite a hard life, how she combined high idealism with practicality, and the extraordinary diversification and emotional range of her writing from children’s books to pulp fiction, adult novels, and nonfiction.

Greg Eiselein

| © David MayesFounded in 2010 by this author, the Louisa May Alcott is My Passion website makes my own feelings clear. The site fosters a worldwide community of Alcott enthusiasts and has become an online hub for devotees and researchers. Thousands visit each year to learn about Alcott family lives and read commentaries on Louisa’s life and writings.

Physician and author Lorraine Tosiello is inspired by Louisa’s “social activism, her devotion to the underdog, and her fight for just causes.” Dr. Tosiello has published two historical fiction novels on Alcott.

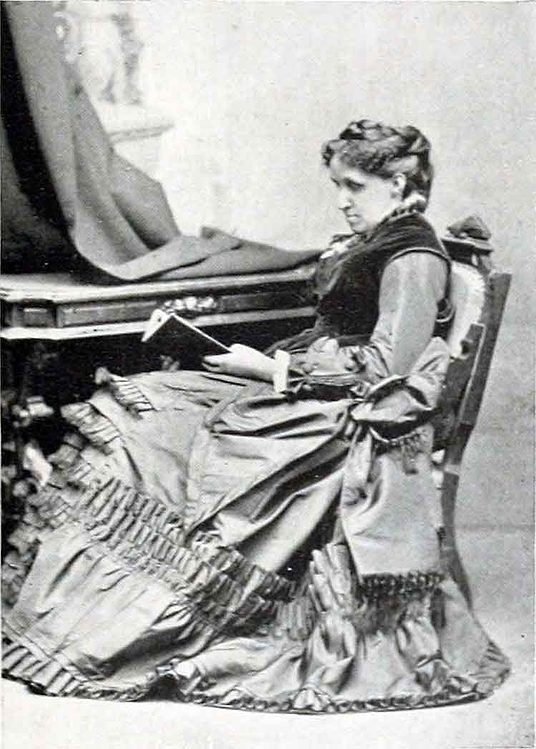

Jennie Watters

| ©Corrie PoppElizabeth Nolan Connors, Director of Learning Resources and Student Support at Dedham Country Day School, was drawn to Louisa’s feminist themes from an early age. Connors volunteers at Orchard House. Jennie Watters, a tour guide there since 2010, admires how Louisa and her family defended human rights, protected nature, and fostered a love of learning in their community. “They will always be relevant because there will always be a struggle for justice,” she said.

Carilyn Calwell-Rains, Director of School Health Services in the Plymouth Public Schools, appreciates Louisa’s commitment to serving others. “It was her exceptional qualities of giving and selflessness—what she did in her life for others,” she said.

Louisa May Alcott was a courageous and complex individual who dared to live outside the norm of nineteenth-century womanhood in order to care for her family through her writing. She and her sisters, Anna, Lizzie, and May, were raised on their parents’ progressive spiritual views, translating into what Louisa referred to as “practical Christianity:” that of taking care of one’s neighbor through self-denial. The girls were afforded opportunities usually denied to Victorian women: education, creativity, self-expression, and the possibility of a career. All the sisters were avid readers, as evidenced by the 60 or more references to various authors in Little Women. The Alcotts battled chronic poverty until Louisa realized her great success in 1868. In her 55 years, Louisa was a devoted daughter, breadwinner, caretaker, homemaker, actress, army nurse, abolitionist, women’s rights advocate, world traveler, and best-selling author. She was also a single mother, as she legally adopted her sister May’s infant daughter after May died only six weeks after giving birth. It is no wonder that those obsessed with Alcott’s life and work are inspired by this captivating individual.

Turnquist beautifully sums up Alcott’s legacy. “In troubled times Alcott’s characters tell one another, ‘Let me help you bear it.’ That generosity is felt by readers. In Louisa, they find someone who ‘gets’ them. Suddenly, they don’t feel alone. They’ve met a soul mate who has offered simple, direct access to the core of her being and, in so doing, offers courage and strength. Humbly, she teaches us to face life, trusting that who we are—flawed as we may be—will be enough.”

I wish to thank Jan Turnquist for proposing the idea for this article, and for her enthusiastic collaboration.