The list of Concord abolitionists is long, and the names of Thoreau, Alcott, Bigelow, and Brooks are assured in the town’s history. But for every famous name involved in abolitionism, many more remain forgotten. One of Concord’s heroes, while not exactly lost to history, is certainly not a household name: he was the Reverend Daniel Foster. Minister, abolitionist, Transcendentalist, and soldier, Foster continually put his career in jeopardy and ultimately died for his beliefs. He was, perhaps, the most radical of them all.

Born in Hanover, New Hampshire, on December 10, 1816, to a family of eight sons and one daughter, Daniel was the fourth of nine children. Seven of the boys would attend Dartmouth College; six of them would become Congregational pastors. However, Daniel left Dartmouth in 1841 before graduating and headed west to Kentucky, where he taught school for two years. Kentucky was a slave state, and he would write in his diary that he “became an abolitionist from a settled conviction of the inherent sinfulness of Slavery, a conviction forced upon me by what I saw of the evil-workings of the system.”

Foster returned to New Hampshire in 1843 and finished his degree at Dartmouth in 1845. He was ordained two years later and served as pastor at several churches in New Hampshire and Massachusetts. Like his ministerial contemporaries, Theodore Parker and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Foster’s abolitionism was unrelenting, and his constant sermons on slavery aroused the anger of many of his parishioners, leading to early dismissals from his churches.

Foster’s sermon book, now in the Massachusetts Historial Society

In 1851, after being asked to leave yet another church, this time in Chester, Massachusetts, Foster accepted the pastorate at the Trinitarian Church in Concord. As he and his family settled in at the Thoreau boarding house on Main Street, they became well acquainted with Concord’s abolitionists, including Mary Merrick Brooks, Ralph Waldo Emerson and the Thoreau family. Foster’s wife Dora, in particular, became good friends with Thoreau’s sister, Sophia.

Things were rocky for Foster at the church. Not only did his abolitionism cause trouble with his congregation, but he openly outed himself as a Unitarian when he gave a sermon entitled, “The Bible; Not an Inspired Book”. Thoreau would mention in his journal that Concord’s Dr. Bartlett considered Foster to be “an infidel,” and he was not alone in that assessment; Foster’s ministry at the church lasted only a year. Thoreau, however, admired Foster, saying that the minister was “frank and manly,” while Emerson would remember Foster as a “brave, good pastor” with “certain heroic traits,”

Despite his congregation’s frustration, Foster refused to soften his abolitionist stance, writing in his diary, “I feel a good deal anxious for I learn that some of the people are dissatisfied…because I make reference often to slavery. And so I…prepare sermons…in the hopes that they will convince these people of their errors and my truth.”

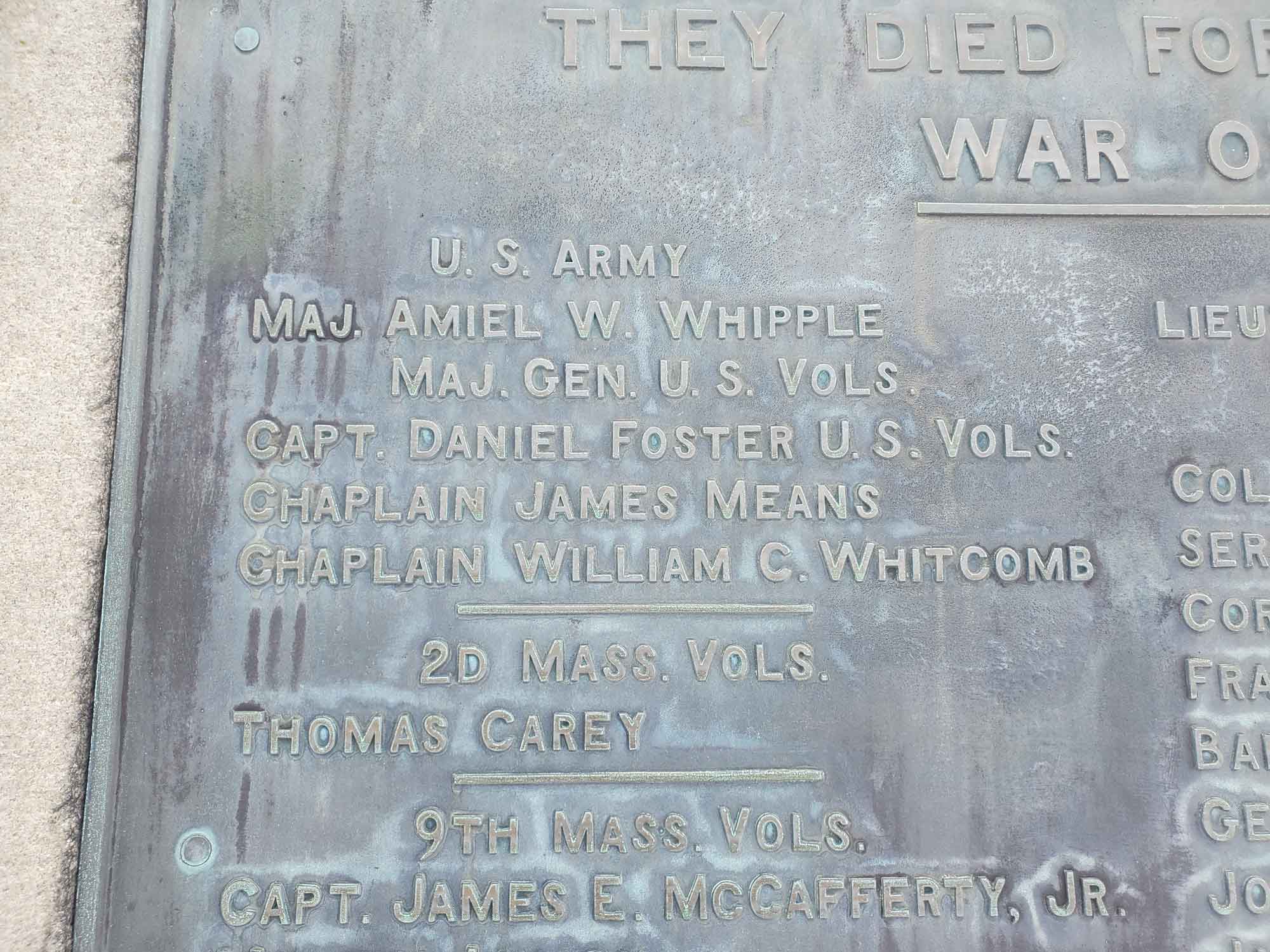

Foster’s name on the Concord Civil War memorial

The compromise of 1850 created a stronger Fugitive Slave Act, and Foster was appalled at the “abhorrent” legislation. He wrote dejectedly about the new law, “Oh my country, how hast thou fallen in this abject hour from thine elevation of honor into the deepest shame and crime.” And, sounding very much like his friend Henry Thoreau, he added, “I renounce and cast off all allegiance to our wicked government.”

In April 1851, Thomas Sims, an escaped slave from Georgia living and working in Boston, became a victim of the new law and was arrested by Federal marshals. Foster, angered at Sims’ arrest by what he called “the hellhounds...in the employ of the slave power,” joined hundreds of demonstrators in Boston for an all-night vigil and was asked to lead them in prayer as Sims was led to the ship for deportation back to Savannah. The prayer, in which Foster asked God to “destroy the wicked power which rules us,” brought him some notoriety and was published in many newspapers. Henry Thoreau wrote approvingly of it in his journal: “The man who made the prayer...was Daniel Foster of Concord. I could not help feeling a slight degree of pride because of all the towns in the Commonwealth, Concord was the only one distinctly named as being represented in that tea-party…”

Foster, in return, greatly admired Thoreau. When Walden was published in 1854, Foster bought a copy and enthusiastically read it aloud to his family.

Daniel was next employed as a lecturing agent with the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. In his first year alone, he lectured 300 times in 87 different locations and raised $400 for the organization. But there were soon disagreements between Daniel and William Lloyd Garrison, and Daniel ended up quitting his job and leaving the Society in 1853.

In 1857 he became the chaplain of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, and it was there that he heard a speech by John Brown about Brown’s anti-slavery activities in Kansas. Like his friends Thoreau and Emerson, Foster became enamored with Brown; in a letter to a friend, he announced that he was “…convinced that our cause must receive a baptism of blood before it can be victorious. I expect to serve in Capt. John Brown’s company in the next Kansas war, which I hope is inevitable & near at hand.”

Foster was as good as his word. In April 1857, he attended a meeting of the Kansas Aid Committee of Massachusetts, an organization whose members included Frank Sanborn of Concord, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, and George Luther Stearns, all future members of John Brown’s “Secret Six.” Foster spent the next couple of years shuttling between Kansas and Massachusetts as an agent for the Committee, teaching school in Kansas and returning to Massachusetts on occasion to give anti-slavery lectures to raise money for the Free Soil settlers back in Kansas.

When the Civil War began in 1861, Daniel was back in Massachusetts, along with Dora and their four children. On August 13, 1862, he enlisted as a chaplain in the 33rd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. He resigned a year later and, in 1864, was commissioned a Captain in the newly formed 37th Regiment of U.S. Colored Troops.

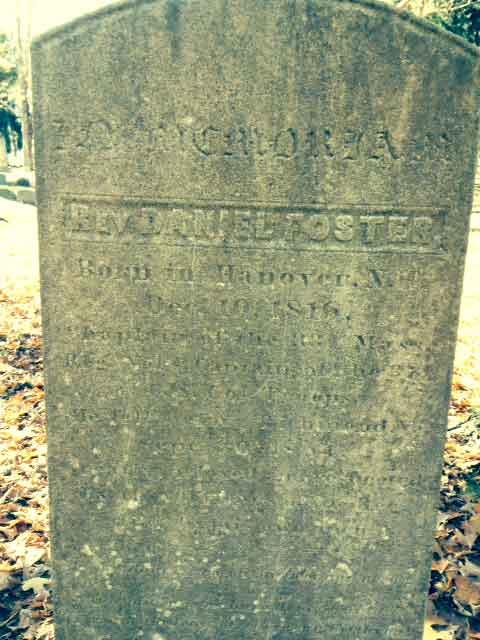

Foster’s grave in West Newbury, MA

The regiment was at the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm near Richmond on September 30, 1864, when Foster and his company were sent forward to “test the enemy lines.” Some of the men went too far in advance and Foster was off searching for them when he was shot in his left side, just above his hip. He managed to stay on his horse and return to his regiment where, just before he died, he asked his men, who had laid him on the ground, to turn him around “as he had vowed that he would die facing the enemy.” Daniel Foster was 47 years old.

Foster’s men and fellow officers raised the money to send his body home to his family. He was buried in Merrimack Cemetery in West Newbury, Massachusetts. Part of the inscription on his tombstone speaks of his devotion to his men and to the cause for which he gave his life:

Greatly beloved and respected by the Officers of the Regiment and by his own men. Friend of the poor and needy.

“Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.”