“Perhaps some of these summers we may see a band of pilgrims coming up to our door…”1 Louisa May Alcott wrote in 1874 to the Lukens sisters, five girls living in Pennsylvania who had begun a pen pal correspondence with their favorite author. Yet despite the invitation, none of the sisters came to Massachusetts in Alcott’s lifetime. In July 2022, I am the pilgrim instead, threading through the apple trees in front of a familiar brown three-story house in Concord, making my way to Alcott’s home for the first time.

Although I have studied Alcott for over 10 years, developed a podcast about her life, and given presentations at museums and libraries, this is the first time I have visited the places most closely linked to her life. Until now, Concord existed only on the page, a place built of letters and words rather than earth, wood, and brick. Logically, I knew it was out there; Massachusetts, while a good distance from my Wisconsin home, is not impossible to reach. Yet because I am separated from Alcott by the distance of time, the places where she lived, worked, walked, and wrote had always seemed inaccessible to me as well.

Still, here I am on a sweltering summer morning in the town where Alcott lived most of her adult life, intent on following her as closely as I can. Of course, no place can be exactly replicated, no pilgrimage can transport me back in time. Standing in front of Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House Museum, I hear cars zipping past on Lexington Road and a lawn mower growling in the distance, both belonging to a soundscape Alcott never knew. Yet the road still follows the same route she walked to catch the train to Washington, D.C. to serve as a nurse during the Civil War, wondering when she would return. The house I’m about to enter is the same as the one she called “Apple Slump,” the house that “summer, pictures, books, and ‘Marmee’ made…lovely,” now as famous as Alcott herself.2

As I walk through Orchard House, stories from her letters and journals unspool before me. In the kitchen I recall the letter she wrote to her friend Alf Whitman about how the cat climbed up her back, causing her to trip over the poker and spill the rice pudding that “none of us like,” while her sister May “set up a cry of victory and danced about the mournful ruins.”3 Standing here, the scene transforms from a written anecdote into a vivid memory. In this house, she recovered from typhoid fever, the abolitionist John Brown’s family visited, Frank Sanborn’s students sang and danced the nights away, filling the rooms with music. Here is where she read the draft of her first novel, Moods, to her family after weeks of non-stop writing in her room, elated “to have my three dearest sit up till midnight listening with wide-open eyes…”4 I look around, wondering where they sat, imagining the dark house lit with flames and words. Upstairs in Alcott’s bedroom, the owl May drew on the mantel and the calla lilies painted on the wall still guard the place where she wrote Little Women, her most beloved novel. I pause in the hallway, curious to see if I can feel her here, but instead of spirits, all I sense are stories, the ones she wrote and the ones she lived.

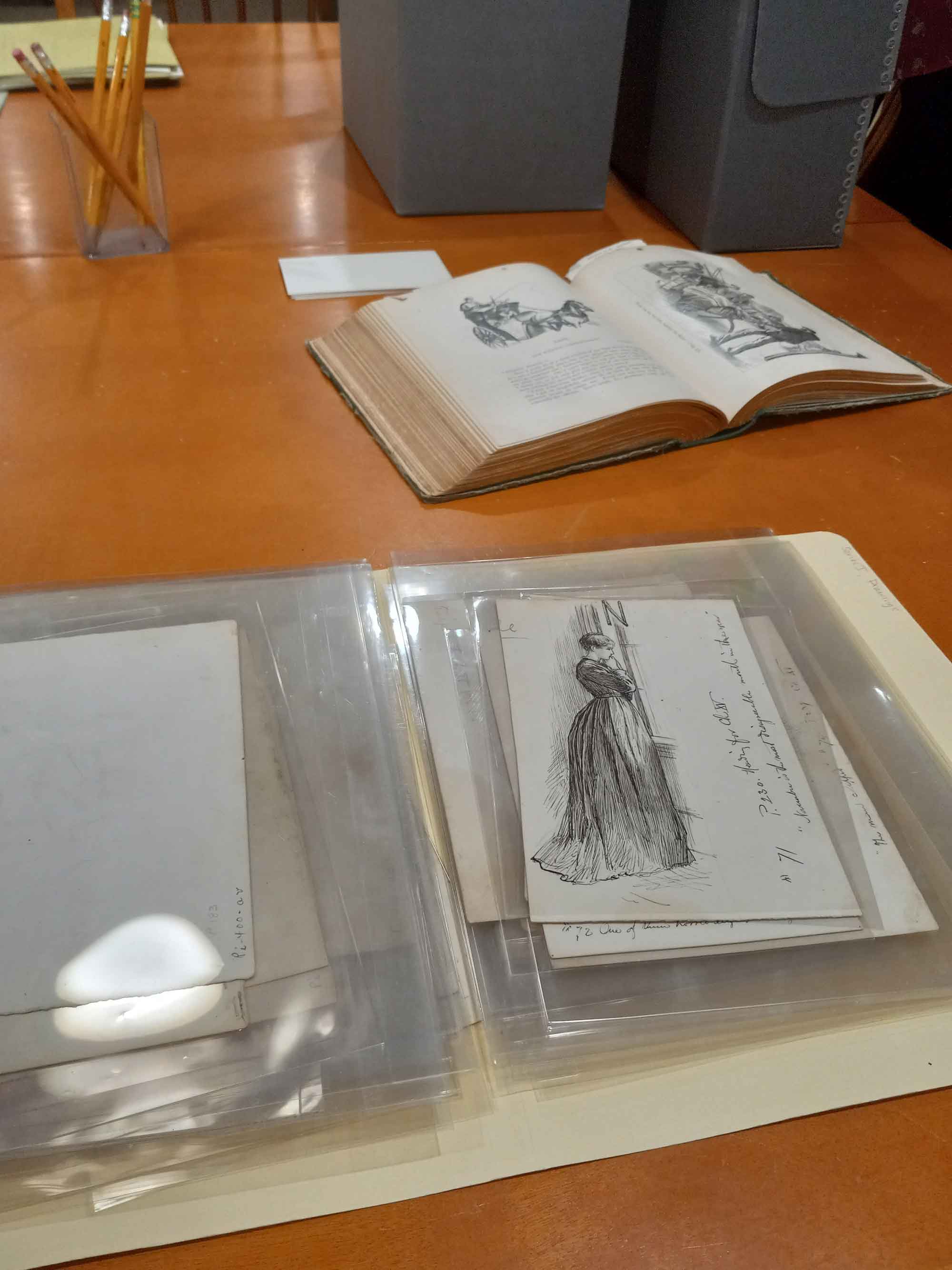

Original illustrations created for Little Women

| ©Jill Fuller

During my week in Concord, Alcott’s life is mappable, her paths traceable. I learn not by reading, but by walking and following, observing distance and space, smell and touch. Downtown, I pass the Italianate brick Town Hall building on Monument Square where Alcott voted in the school committee election of 1880, the first in town to allow women voters. I take pictures of the Thoreau-Alcott house on Main Street where she held suffrage meetings, started a Temperance Society, and where her beloved mother Abigail died. My family and I swim at Walden Pond as Alcott did with her sisters and friends, and see Ralph Waldo Emerson’s home on Lexington Road, whose library Alcott frequented when she lived at Hillside (now the Wayside), just down the street. After years of reading about Emerson’s influence on her life, seeing the location of both houses helps me better understand how the short distance between them made possible a steady flow of Emerson’s books and ideas to an impressionable teenage Alcott. I climb the stairs to the attic bedroom of the red farmhouse at Fruitlands Museum in Harvard, Massachusetts, where she lived in her father’s utopian community when she was ten and eleven. In her journals, a young Alcott recorded many nights in that space, watching the moon, listening to the rain, reciting poetry, and crying from anxiety and exhaustion. The sorrows of the room hang as heavy as the heat and after only a few moments, I turn to go.

My pilgrimage continues down a flight of stairs and through a glass door into the William Munroe Special Collections at Concord Free Public Library. My stomach twists in excitement as a librarian carefully pulls out archival boxes and file folders containing original chapters of Little Women and Frank Merrill’s 1880 illustrations for the novel with Alcott’s comments on the back. Her handwriting blooms from the pages. Penciled at the bottom of a Little Women chapter is the note “Saved by mother’s desires”; on an illustration of the March sisters, she wrote, “Good, but Jo is always made to look too old for her years.” Time folds in on itself as I turn over pages she once held, the distance between us shrinking with a few pieces of paper.

Louisa May Alcott’s grave at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery

At Author’s Ridge in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, my family and I place a pen beside Alcott’s marker. An American flag flutters in recognition of her Civil War service. I kneel there for a few moments but do not linger. Quietly, I greet her family buried next to her, then I wander down the cemetery’s paths crisscrossed by tree roots, stones hidden around corners. The place is a labyrinth of stories. Alcott came here too, for Thoreau’s burial, for her sister Lizzie’s and her mother’s. This was the place where she said goodbye to the people she loved. “Death never seemed terrible to me,” she wrote to her friend Maggie Lukens in 1884. “If in my present life I love one person truly… I believe that we meet somewhere again, though where or how I don’t know or care, for genuine love is immortal.”5 As I make my way to Emerson’s grave, I don’t think of her buried under a stone. I imagine her standing where I am now, listening to the trees creak in the wind, our steps overlapping as we both turn and journey on.

1 Louisa May Alcott, The Selected Letters of Louisa May Alcott, ed. by Joel Myerson, Daniel Shealy, & Madeleine B. Stern. (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1995), 177. 2 Ibid., 228. 3 Ibid., 47. 4 Louisa May Alcott, The Journals of Louisa May Alcott, ed. by Joel Myerson, Daniel Shealy, & Madeleine B. Stern. (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1997), 104. 5 Alcott, The Selected Letters, 279.

.jpg?height=1200&t=1721321264)