Henry David Thoreau’s younger sister, Sophia Elizabeth Thoreau (1819–1876), was a botanist, artist, editor, and abolitionist who worked as a teacher and managed the family’s pencil business. She significantly shaped her brother’s legacy to an extent that modern scholars argue was under-acknowledged by Thoreau’s early biographers. Sophia Thoreau was the youngest child of Cynthia Dunbar Thoreau and Concord storekeeper and pencil maker John Thoreau. Henry and Sophia, who lost their brother John in 1842 and their sister Helen in 1849, became even closer companions after the family’s losses.

Henry D. Thoreau began keeping a journal in 1837, recording his experiences and observations. The Journal served as source material for published essays, poems, translations, and two books during his lifetime - A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849) and Walden (1854). Nonetheless, he attained only limited recognition in his own time. This made Sophia’s efforts, especially in her role as executor of his estate, to safeguard his possessions and voluminous manuscripts after his death particularly significant. The great majority of Henry D. Thoreau’s writing was published after his death. This was largely due to her devotion, editorial skill, and tireless efforts to keep his manuscripts in order and selecting an editor for her brother’s Journal.

The significant Thoreau artifacts in the Concord Museum’s holdings also came directly or indirectly to be in the collection thanks to Sophia.

The early editions of Henry David Thoreau’s posthumous publications, Excursions (1863), The Maine Woods (1864), Cape Cod (1865), and A Yankee in Canada, with Anti-Slavery and Reform Papers (1866), listed no editors. Early Thoreau biographers credited Ralph Waldo Emerson and Thoreau’s friend and poet Ellery Channing with putting these editions together and seeing them through publication. More recently, due to the study and interpretation of the definitive edition of The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau, a project inaugurated in 1966 and published by Princeton University Press, scholars have recognized Sophia’s key role as editor of these posthumously issued volumes. Furthermore, Sophia was Henry’s caretaker while he was suffering the terminal effects of tuberculosis; Sophia helped him revise manuscripts of essays that appeared in the Atlantic Monthly in the months following his death in 1862, including the essay “Walking,” based mainly on journal entries for 1850-1852, which he had delivered as lectures in the mid-1850s.

When Sophia moved to Bangor, Maine, in 1873, she eventually deposited her brother’s manuscripts in the Concord Free Public Library, under Ralph Waldo Emerson’s supervision. At the same time, she gave the Library many books that had belonged to her brother. Through her generosity, the Concord Free Public Library holds the most extensive intact collection of volumes once part of Henry Thoreau’s personal library, valuable for scholarship because they shed light on influences on Thoreau’s thought and his engagement with reading.

Sophia died in 1876 at 57, having long suffered from ill health. According to her will, author and editor H. G. O. (Harrison Gray Otis) Blake inherited Thoreau’s manuscripts, except for Thoreau’s nearly 200 land and property surveys and surveying field notes, which became the Library’s.

On H. G. O. Blake’s death in 1898, E. Harlow Russell of Worcester inherited Thoreau’s manuscripts. Russell sold the literary rights to Houghton Mifflin in Boston for the publication of the Journal and also negotiated the sale of hundreds of manuscript pages. In 1904, Russell sold the remaining Thoreau manuscripts to dealer George Hellman, who broke them up to sell them more profitably than they could be sold as a lot.

Due in large part to Sophia’s initial care of Thoreau’s trove of manuscripts, numerous other posthumous publications were realized. They included Ralph Waldo Emerson’s edited letters (Letters to Various Persons, 1865); the four seasonally arranged selections from the manuscript journal made by H. G. O. Blake—Early Spring in Massachusetts (1881), Summer (1884), Winter (1888), and Autumn (1892); Poems of Nature (1895), selected and edited by Henry S. Salt and Frank Sanborn; the fourteen-volume first publication of most of the Journal in the 1906 Manuscript and Walden Editions of the author’s complete works, edited by Bradford Torrey and Francis Allen, and the Princeton University Press Edition, The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau, currently edited by Elizabeth Hall Witherall, comprises the complete and authoritative texts of the works of Thoreau (1817–1862), including previously unpublished essays, correspondence, and journals, as well as editions of his best-known titles.

Sophia ensured that other items significant to preserving her brother’s legacy were also kept and accessible.

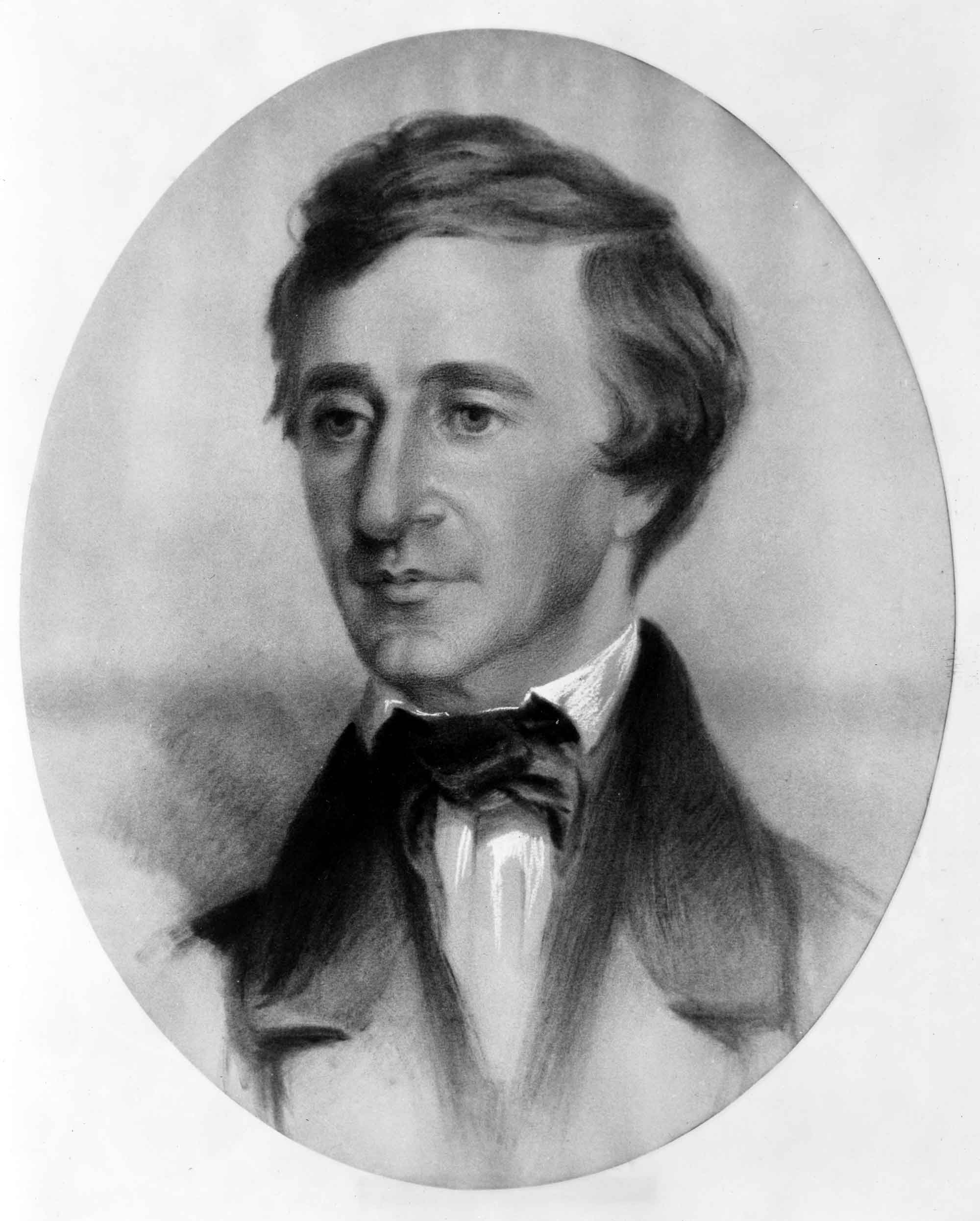

Henry David Thoreau (1854) by Samuel Worcester Rowse. Crayon portrait in the Concord Free Public Library Corporation Art Collection. Original from the bequest of Sophia E. Thoreau, 1876/1877.

| Courtesy of the Concord Free Public LibraryIn the Thoreau Room at the Library hangs a copy of Samuel Worcester Rowse’s crayon portrait of Henry David Thoreau. The original from the bequest of Sophia E. Thoreau is held in the William Munroe Special Collections. The 1854 Rowse crayon portrait, prominently displayed in the Concord Free Public Library reading room in the late nineteenth century, is one of only three significant portraits of Thoreau during his lifetime. It was sketched in the summer of 1854 when Thoreau’s Walden was first published. Samuel Worcester Rowse was a well-known mid-nineteenth-century painter, illustrator, and lithographer. In the summer of 1854, he came to Concord to draw a portrait of Emerson. Boarding with the Thoreaus, he was asked by Mrs. Thoreau to draw a portrait of her son Henry, too.

Courtesy of the Concord Free Public Library

Courtesy of the Concord Free Public Library

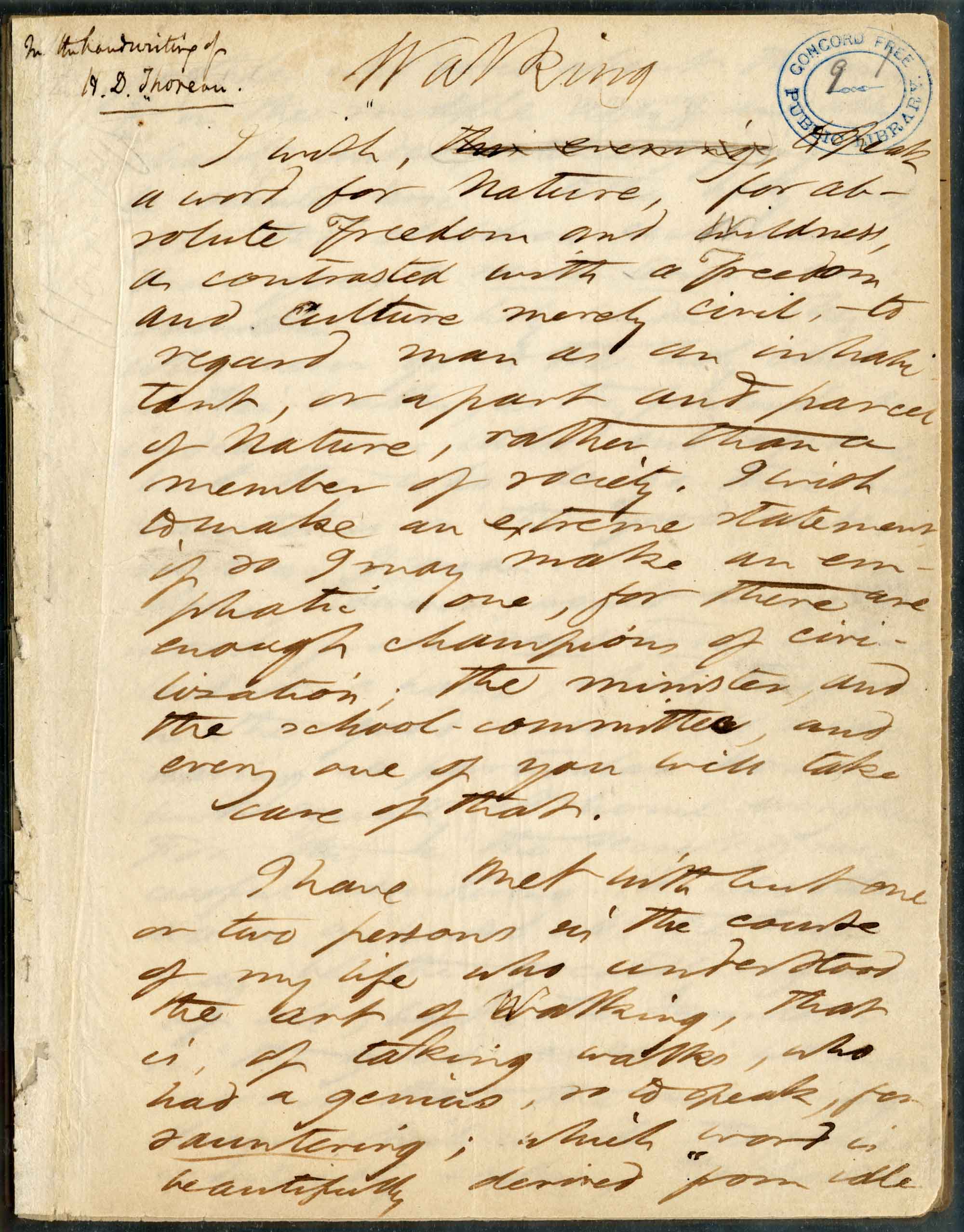

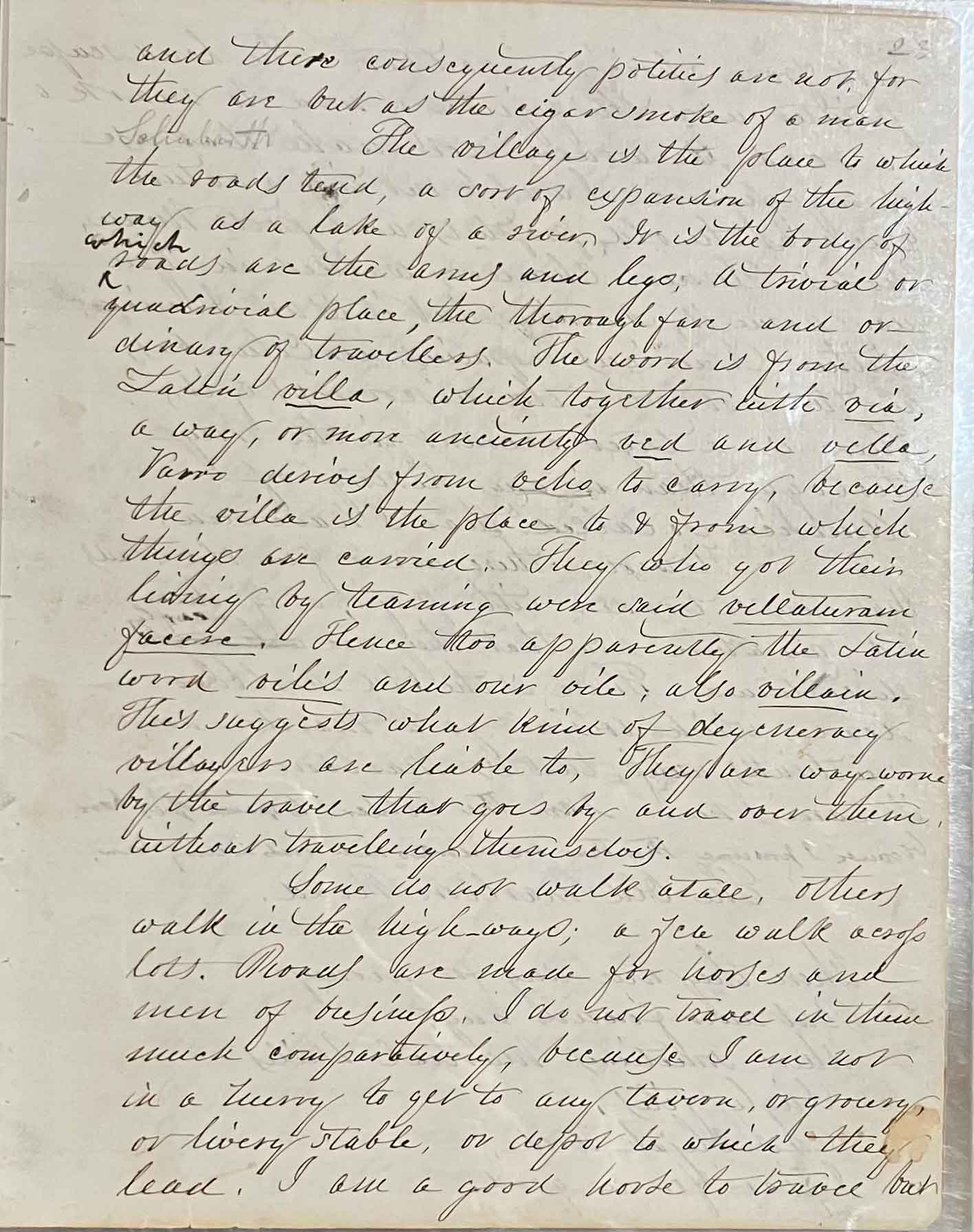

Manuscript of “Walking,” published in Atlantic Monthly for June 1862 (v. 9, no. 56) and later in the collection, Excursions (first published in Boston by Ticknor and Fields, October 1863). The manuscript contains numerous deletions and emendations by Thoreau; portions of it are in the hand of Thoreau’s sister Sophia.

| Courtesy of the Concord Free Public Library

Thanks to an 1873 gift by James T. Fields in honor of the opening of the Library, Special Collections also holds the 1862 publisher’s manuscript of “Walking,” published in Atlantic Monthly for June 1862 (v. 9, no. 56) and later in the collection Excursions (first published in Boston by Ticknor and Fields, Oct. 1863). This manuscript of “Walking” contains numerous deletions and emendations by Thoreau; and in one of the pages selected here, also shows evidence of Sophia’s close collaboration with her brother, as portions of it are in her hand.

The William Munroe Special Collections at the Concord Free Public Library holds the largest and most important collection of primary Thoreau material in New England and extensive collections documenting Concord as Thoreau knew it.

Other significant collections of Henry David Thoreau manuscript material are found in the Houghton Library (Harvard University), the Abernethy Library (Middlebury College), the Berg Collection (New York Public Library), the Pierpont Morgan Library, and the Henry E. Huntington Library.

.jpg?height=1200&t=1723651553)